A Train of Powder gave me my first taste of Rebecca West’s work, and it was incredible from sentence one. (And speaking of sentences, this book led to the only time in memory that I can recall noting a sentence as one of the best I’ve ever read.) She makes incredible, and incredibly smart, connections, proving herself an unbelievably imaginative thinker. At one point, she describes a lawyer’s speech as “superb,” “as free from humbug and tricks as Euclid, and it lived in the memory by its logic and lucidity,” and she might well have been describing her own prose styling; I had, in fact, previously listed lucid and logical (alongside witty) as descriptors to use in this review. She routinely utilizes wonderful turns of phrase, yes, but is also concise in her incisive brilliance, and never flashy.

Even as she writes with both a rhetoric and an understanding that are timeless, nearly every sentence is a reminder that a journalist like West would never be permitted to thrive in the distorted climate of the present day, when readers are all to happy to accept liberties with facts but are nearly always unwilling to allow that a writer has a personal point of view on matters. Not only does she embed her point of view inextricably, but she does not even remove herself and her actions from the reporting. Her approach aside, however, even small concepts and ideas that she incorporates resonate forward in time, let alone the large ones—it’s impossible to read West’s description of post–Second World War Berliners as being “sure that the United States had had most say in [a] matter [over Great Britain and France], for they suspected that the British were on their way down to join the French in the dusk where great powers outlive their greatness” without thinking of the United States having since joined them in that gloom.

It is not as though she were working completely without restraint. She describes the legal restrictions on crime reporting in Great Britain as “far beyond American conception,” and admirable, in their way: “If a gentleman were arrested carrying a lady’s severed head in his arms and wearing her large intestine as a garland round his neck and crying aloud that he and he alone had been responsible for her reduction from a whole to parts, it would still be an offence for any newspaper to suggest that he might have had any connection with her demise until he had been convicted of this offense by a jury and sentenced by a judge.” As a result, the passion of reporters and editors “seeps into the newsprint and devises occult means by which the truth becomes known,” allowing readers to “learn with absolute certainty, from something too subtle even to be termed a turn of phrase, which person involved in a case is suspected by the police of complicity and which is thought innocent.” Four of these dispatches were written originally for The New Yorker, and so West was not necessarily subject to such standards, but nevertheless at time chooses to alter the angle of her portrayals, not so much to subtly impart her opinion as to formally highlight the arbitrariness of not being able to state it more openly. A delicious example of judgement by way of hypothetical: “Had the outburst been simply an unlovely piece of hypocrisy, based on a profound contempt for his fellow men, it would have sounded much the same; and it would have sounded equally irreconcilable with liberalism as that word is generally understood.” (Elsewhere, in less delicate circumstances, she might feel comfortable openly expressing less specific, and less charged, opinions, for example, noting that the making of a certain mistake “was a measure of the lightly furnished state of the boy’s mind,” or describing a radio telegraphist “whose every word betrayed a simplicity of mind so great that its effect was as disconcerting as complexity.”)

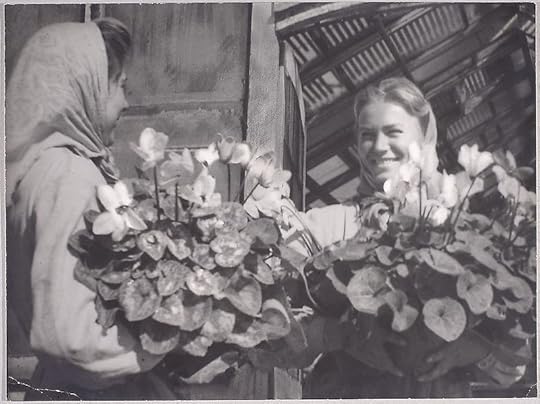

There is a deep consistency to West’s thinking, so much so that in “Greenhouse with Cyclamens III,” when she quite logically made an oblique reference back to a previous installment, I was thinking that it was a reference to one of the unrelated pieces, so closely would the same construct, the same perception, have fit another of the scenarios. The key to this consistency is that she joins her intelligence with a deep humanism, and a deep humanity, which she masterfully allows to coexist with an equally deep understanding of the inexplicability of human behavior; as a result, she necessarily had to embrace the accompanying ambiguities that perhaps more than ever surface when it comes to matters of guilt and punishment. She notes that “[t]he position of man is obviously extremely insecure unless he can find out what is happening around him. That is why historians publicly pretend that they can give an exact account of events in the past, though they privately know that all the past will let us know about events above a certain degree of importance is a bunch of alternative hypotheses.” West understood that these ambiguities were at the heart of the stories she was telling (see her summation of the wife of a convicted accessory to murder: “What amazed her was the incongruity between the facts which the police told her about her husband and what she herself knew about him. [...] She did not deny that what the police said was true, she simply made a claim that what she knew was also true.”); to resolve them would be beside the point, and likely even diminish the power of the reporting.

More than anything else, A Train of Powder gives one the sense of being in good hands, and more than that, even manages to dispense with the usual accompanying feeling, one of continued fervent hope that the author will manage to keep progressing forward without making a mis-step. Here, any such fear was dispelled rather quickly, and even after that point, West keeps pulling from her literary carpet-bag, showing off her brilliance in deftly misdirecting the reader’s focus; waiting until just the right moment to disclose certain information; and repeatedly topping herself when it comes to producing the perfect button to cap off a paragraph, section, or piece (or book—indeed, the very last sentence here once again references those ambiguities: “But it can be said of this larger mystery only what can be said of the lesser mystery [...]: the facts admit of several interpretations.”). I savored every moment of it.