What do you think?

Rate this book

960 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published January 1, 1968

The well-dressed businessmen. The luxurious clubs, they're as good as any in Europe. The gaiety of a first-class fiesta. Good hotels, good restaurants, good entertainment. A substantial city that seems to be well run ...

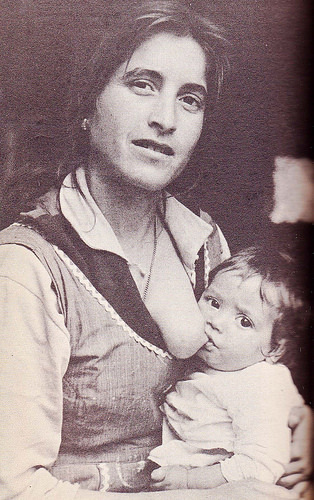

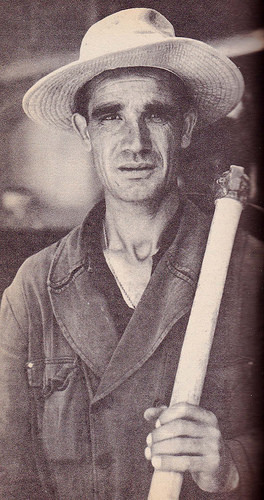

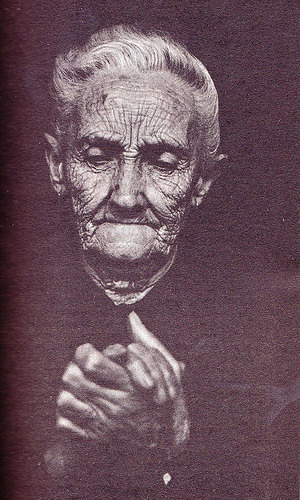

But as I rode out to the port to rejoin my ship for the long haul back to Scotland, I could not help recalling the peasants of Teruel and the abysmal and almost terrifying poverty that was their lot. Between these two Spains, and remember that I had not yet seen the superarrogant nobility of Sevilla, there existed such a gap that I simply could not bring it into focus ...

To fuse the rural peasant of Teruel and the rich clubman of Valencia lolling in his leather chair after a gorging meal was for me impossible, and I began at that moment to formulate that series of speculations regarding Spain which were to exercise me for the next decades. Whenever I read about Spain it was to find answers to these questions, and remember that they were posed some years before the Civil War disfigured the country.

The biggest social differences between then and now is the radical change effected by what a Spanish man called ‘the revolution of the Sueca.’ … [The author told by a businessman that the term was used to refer to “the Swedish girls” (also Finns, Norwegians, Danes, Germans), who discovered Spain “and flocked down here by the planeload”] Their first impact was on the beaches, and once they stripped down to their bikinis and we saw what the human body could be, the old laws [a society rigidly obeying “puritanism”, “but much stronger than yours in the States, because here the whole society supported it”] simply could not be enforced.And Michener goes on for two pages about how a revolution in morals began to occur. (395ff)

Well, the first result of the Sueca invasion was cataclysmic.

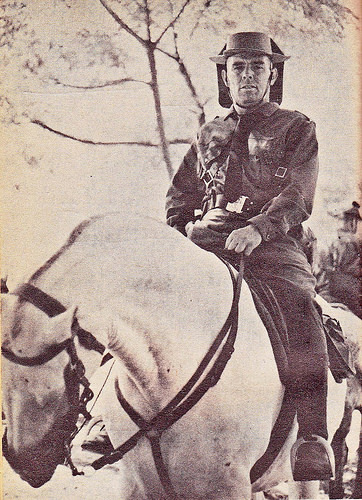

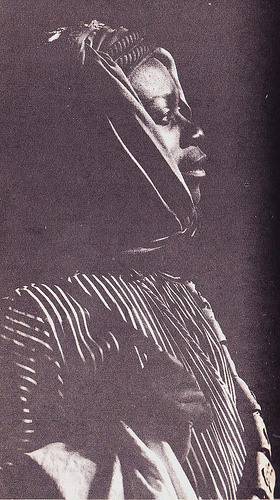

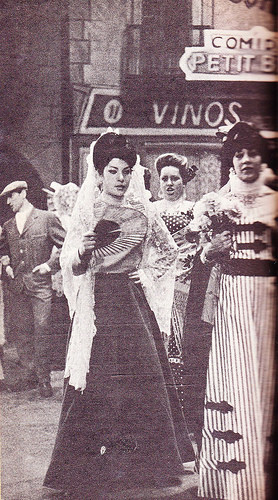

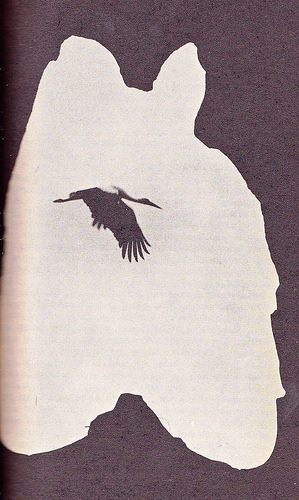

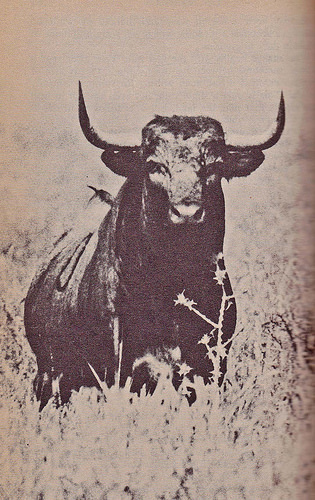

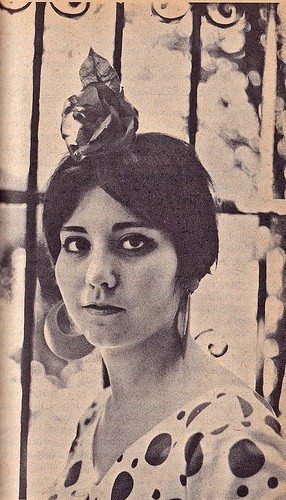

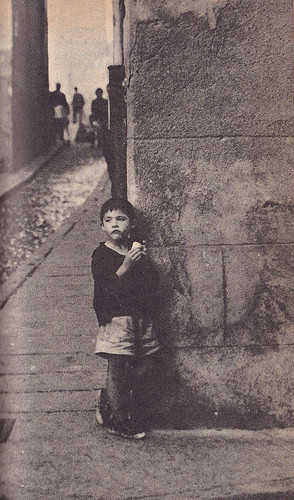

I remember the commission we agreed upon: ‘Vavra will go over Spain guided only by his own eye, completely indifferent as to what Michener may write or think or prefer. Shoot a hundred of the very finest pictures he can find and make them his interpretation of Spain. If he can succeed in this, the pictures will fit properly into any text.I have not counted pictures in the book, most but not all full-page, black and white, all Vavra’s. But they are a wonderful fulfillment of this commission. Here are a few, with captions from the book.

In a sense no visitor can ever be adequately prepared to judge a foreign city, let alone an entire nation; the best he can do is to observe with sympathy.