What do you think?

Rate this book

384 pages, Paperback

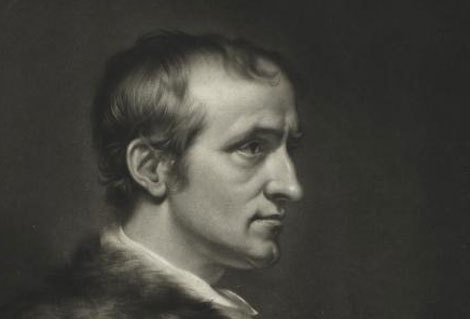

First published January 1, 1794

At different moments, the book bears resemblance to a wide variety of other works: here it’s the clever political thriller of Graham Greene (The Power and the Glory), there it’s the adventure thriller of John Buchan (The Thirty-Nine Steps), elsewhere it’s the survivalist tale of Geoffrey Household (Rogue Male), or the late Tolstoy (Resurrection and After the Ball), then Dostoevsky, and in one version of the ending—straight-up Beckett.

And in comparison to nearly all these authors, Godwin comes out on top.

The book is fundamentally built on the thesis that political violence by the state is not merely a function of the state itself but permeates the fabric of life in all interpersonal relationships.

Remarkably, although almost every sentence in the book serves a philosophical purpose, it never feels didactic, moralizing, sentimental, or illustrative.

The combination of spontaneous psychological impact with a rationally organized philosophical narrative observed here feels, to me, utterly unprecedented—only Conrad at his finest moments could be placed alongside it.

Godwin’s political convictions, as far as I understand, were quite firm and well-defined, yet the ending doesn’t lead to any specific conclusions; in the moral confrontation, he refuses to name winners—a further testament to his belonging to the lineage of artists rather than illustrators.

I’d venture to explain Godwin’s relatively marginal position in the literary canon by suggesting that the canon simply fears admitting such a bold and powerful book, whose presence makes the fragility and timidity of established canonical works all the more apparent.