What do you think?

Rate this book

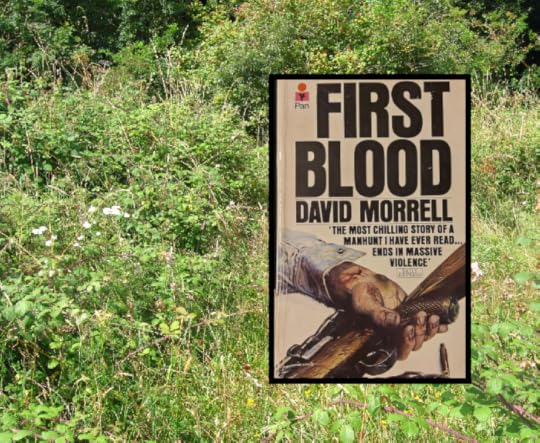

316 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1972

Excerpts

"Sure you'll fight. Sure. What a laugh. Take a look at yourself. Already you know what this place reminds you of. Two days in that cramped cell and you'll be pissing down your pant-legs. 'You've got to understand I can't stay in there.' He could not stop himself. 'The wet. I can't stand being closed in where it's wet.' The hole, he was thinking, his scalp alive. The bamboo grate over the top. Water seeping through the dirt, the walls crumbling, the inches of slimy muck he had to try sleeping on. Tell him, for God's sake. Screw, you mean beg him."

" 'Green beret?' Lester said. The voice was starting to repeat, broke up, never came back again. It started to rain, light drops speckling the dust and dirt, spotting Teasle's pants and soaking in, pelting cool on his bare back. The black clouds shadowed over. Lighting crackled and lit up the cliff like a spotlight, and as fast as the spotlight came on, it went off and the shadows returned, bringing with them shock waves of exploding thunder. 'Medal of Honor?' Lester said to Teasle. 'Is that what you brought us after? A war hero? A f*****g Green Beret?' "

↻ ◁ II ▷ ↺

0:00 ㅇ─────── 3:26