What do you think?

Rate this book

339 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1982

Nothing sticks to us but smoke in our hair and clothes. It is dead time. It never happened until it happens again. Then it never happened.

This is where I want to be. History. It’s in the air. Events are linking all these countries. What do we talk about over dinner, all of us? Politics basically. That’s what it comes down to. Money and politics. And that’s my job.

Was religion the point or language? Or was it costume? Nuns in white, in black, full habits, somber hoods, flamboyant winglike bonnets. Beggars folded in cloaks, sitting motionless. Radios played, walkie-talkies barked and hissed. The call to prayer was an amplified chant that I could separate from the other sounds only briefly. Then it was part of the tumult and pulse, the single living voice, as though fallen from the sky.

The alphabet is male and female. If you will know the correct order of letters, you make a world, you make creation. This is why they will hide the order. If you will know the combinations, you make all life and death.

We can say of the Persians that they were enlightened conquerors, at least in this instance. They preserved the language of the subjugated people. This same Elamite language was one of those deciphered by the political agents and interpreters of the East India Company. Is this the scientific face of imperialism? The humane face? (80)."Americans choose strategy over principle every time and yet keep believing in their own innocence” (236). Occupation may be the master figure, such as in this counter-Foucauldian dissymmetry of vision: “Does your boss tell you that power must be blind in both eyes? You don’t see us. This is the final humiliation. The occupiers fail to see the people they control” (237). (“White people established empires. Dark people came sweeping out of Central Asia” (260).)

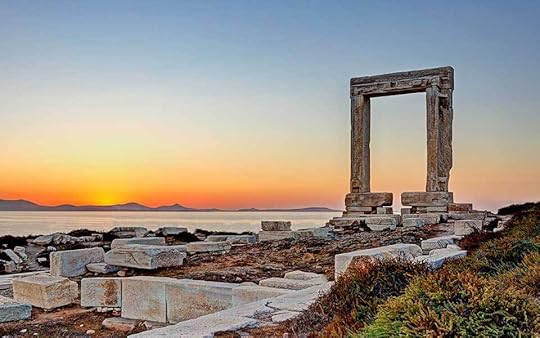

It’s about two kinds of discipline, two kinds of fundamentalism. You have Western banks on the one hand trying to demand austerity from a country like Turkey, a country like Zaire. Then you have OPEC at the other end preaching to the West about fuel consumption, our piggish habits, our self-indulgence and waste. The Calvinist banks, the Islamic oil producers. We’re talking across each other to the deaf and the blind. (193)Opens memorably with a reluctance to go to the Acropolis: “There are obligations attached to such a visit” (3). What relation, then, of this principle to “What ambiguity is in exalted things. We despise them a little” (id.), aside from the notion in Stallybrass & White that disgust always bears the imprint of desire?

the whole thing is written in boustrophedon. One line is inscribed left to right, the next line right to left. As the ox turns. As the ox plows. This is what boustrophedon means. The entire code is done this way. It’s easier to read than the system we use. You go across a line and then your eye just drops to the next line instead of darting way across the page. Might take some getting used to. (23)Not sure what the trigger will be for deployment of this conceit, though the in-setting item sub judice concerns “criminal offenses, land rights and other things.” However: “There was a cosmology here, a rich structure of some kind, a theorem of particle physics. Reverse and forward were interchangeable” (65).

In the tallgrass prairie what you did was work. All that space. I think we plowed [NB] and swung the pick and the brush scythe to keep from being engulfed in space. It was like living in the sky. (77)The ‘sky’ references are very Griffiny (Modernism and Fascism, yo).

Don’t look at my books. It makes me nervous when people do that. I feel I ought to follow along, pointing out which ones were gifts from fools and misfits. (85)“Technicians are the infiltrators of ancient societies. They speak a secret language. They bring new kinds of death with them” (114). Shares the misanthropic fear of Mao II in the “nightmarish force of people in groups” (276).

In this century the writer has carried on a conversation with madness. We might almost say of the twentieth-century writer that he aspires to madness. Some have made it, of course, and they hold special places in our regard. To a writer, madness is a final distillation of self, a final editing down. It’s a drowning out of false voices. (118)Some intertextual traffic with Blood Meridian: “It was a staccato laugh, building on itself, broadening in the end to a breathless gasp, the laughter that marks a pause in the progress of the world, the laughter that we hear once in twenty years” (153).

This space, this emptiness is what they have to confront. I’ve always loved American spaces. People at the end of a long lens. Swimming in space. But this situation isn’t American. There’s something traditional and closed-in. (198)Further, it’s an “extreme way of seeing,” “another part of the twentieth-century mind,” the world seen from inside” (200). “If a thing can be filmed, film is implied in the thing itself” (200), which is kinda cool Kantian language.

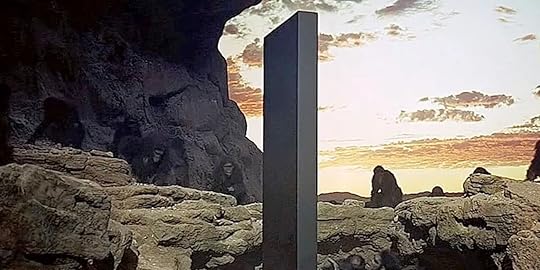

Film is not part of the real world. This is why people will sex on film, commit suicide on film, die of some wasting disease on film, commit murder on film. They’re adding to the public dream [cf. Foucault regarding political dreams!]. (203)The novel’s anagnorisis: “Something in our method finds a home in your unconscious mind. A recognition. This curious recognition is not subject to conscious scrutiny […] We have in common that first experience, among others, that experience of recognition, of knowing this program reaches something in us” (208). And the program? “A place where it is possible for men to stop making history. We are inventing a way out” (209), which strikes me as the great anti-hegelian political dream, to step outside of history—or the great Marxist dream, to come to the end of history.