What do you think?

Rate this book

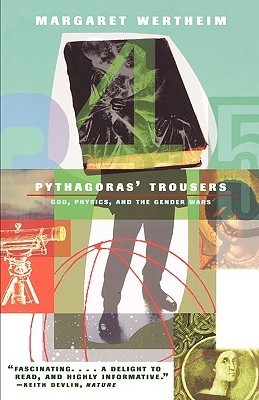

320 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1995

The irony is that today Giordano Bruno is often portrayed by scientists as a martyr—a man who paid with his life for supporting heliocentric cosmology. However, as historian Francis Yates has shown, it was not his views about science that were the problem. The “genuine” physicists of his own time were as much opposed to his ideas as the clerics themselves.