What do you think?

Rate this book

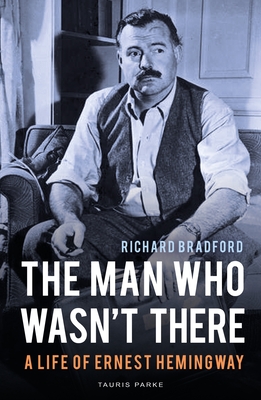

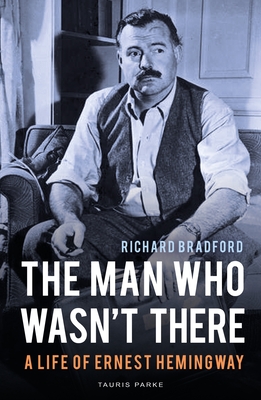

352 pages, Paperback

Published November 3, 2020

An author's success in reframing and disguising reality as fiction presupposes an ability to consciously differentiate between the two. For Hemingway the boundaries between life and writing were sometimes poorly defined.(loc.90)Hem, the book implies, is borderline psychotic and of questionable sanity. I'd have liked far more sourced evidence and close analysis than is provided here to accept this.