What do you think?

Rate this book

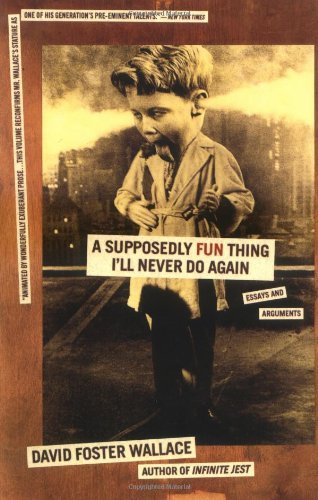

353 pages, Paperback

First published February 1, 1997

come to my blog!

come to my blog!

.

.

«Right now it's Saturday 18 March, and I'm sitting in the extremely full coffee shop of the Fort Lauderdale Airport, killing the four hours between when I had to be off the cruise ship and when my flight to Chicago leaves by trying to summon up a kind of hypnotic sensuous collage of all the stuff I've seen and heard and done as a result of the journalistic assignment just ended»In the absence of a little courage to start the gigantic Infinite Jest, I hit up the lighter and more reassuring humorous essay "A Supposedly Fun Thing I'll Never Do Again". Commissioned to the author by Harper's magazine, this work is a coverage of the "7 nights Caribbean cruise", for a term of a clean week. A luxury cruise only for rich people. The David Foster Wallace's portrait of the typical American on holiday is hilarious, and the the one of the infrastructure and of the cabin crew is excessive and surreal.

The obsession of the entertainment at all costs. The compulsion of the nourishment at all times.

Vote: 7.5

«E allora oggi è sabato 18 marzo e sono seduto nel bar strapieno di gente dell’aeroporto di Fort Lauderdale, e dal momento in cui sono sceso dalla nave da crociera al momento in cui salirò sull’aereo per Chicago devono passare quattro ore che sto cercando di ammazzare facendo il punto su quella specie di puzzle ipnotico-sensoriale di tutte le cose che ho visto, sentito e fatto per il reportage che mi hanno commissionato»In mancanza di un pò di coraggio per iniziare il mastodontico "Infinite Jest", mi butto sul più leggero e rassicurante saggio umoristico "Una cosa divertente che non farò mai più". Opera commissionata all'autore dalla rivista Harper's, si tratta di un reportage della crociera "7 notti ai Caraibi", per la durata di una settimana tonda tonda. Crociera extra-lusso per soli ricchi. Il ritratto che David Foster Wallace dipinge dell'americano medio in vacanza è esilarante, mentre quello dell'infrastruttura e del personale di bordo è eccessivo e surreale.

L'ossessione del divertimento a tutti i costi. La compulsione del nutrimento a tutte le ore.

Voto: 7.5

I have felt as bleak as I’ve felt since puberty, and have filled almost three Mead notebooks trying to figure out whether it was Them or Just Me.

Like most unbearably sad things, it seems incredibly elusive and complex in its causes and simple in its effect: on board the Nadir—especially at night, when all the ship’s structured fun and reassurances and gaiety-noise ceased—I felt despair. The word’s overused and banalified now, despair, but it’s a serious word, and I’m using it seriously. For me it denotes a simple admixture—a weird yearning for death combined with a crushing sense of my own smallness and futility that presents as a fear of death. It’s maybe close to what people call dread or angst. But it’s not these things, quite. It’s more like wanting to die in order to escape the unbearable feeling of becoming aware that I’m small and weak and selfish and going without any doubt at all to die. It’s wanting to jump overboard.