What do you think?

Rate this book

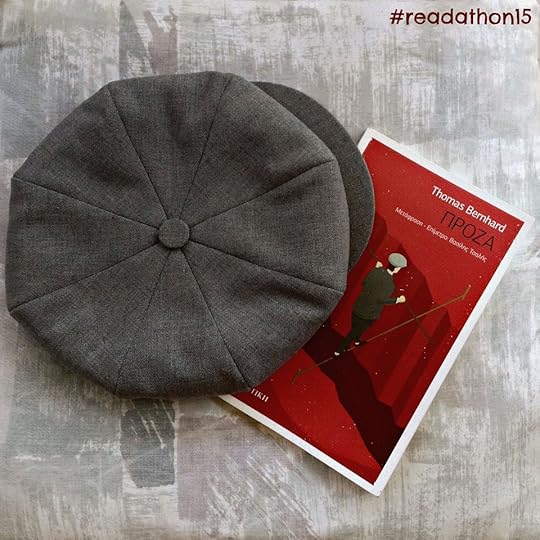

180 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1978

One describes best what one hates, I thought.I was a bit leery approaching these early short stories of Thomas Bernhard, a writer who specialized in monologue-heavy novels, all of which in years past I have assimilated thoroughly and accordingly. But I was pleased to find Bernhard in fine form within these tales, displaying many of what would soon become his trademark stylistic mannerisms. Though not known for employing direct dialogue, Bernhard also shows himself to have quite an ear for it in the story 'Is It a Comedy? Is It a Tragedy?', which comes to center on a charmingly absurd conversation between the narrator and a man he encounters in a city park who happens to be wearing women's clothing. This story was essentially perfect, and all of the others were also either at that level or close to it. I have always admired Bernhard's endings to his novels, and this admiration now extends to these stories, all of which end with seamless grace. As someone who is highly sensitive to the wretched manner in which most short stories end, I read every ending in this collection with an electric thrill of satisfaction coursing through my central nervous system. Yes, I said, yes. (In my head I said this, or if perhaps muttered out loud, then softly under my breath, drawing out the ess at the end almost akin to a hiss [actually no, that's not true—I did nothing of the sort; at most I nodded to myself (in my head, that is)]). Now I wish Thomas Bernhard had written many more short stories, as reading these in lieu of his novels is akin to drinking instant coffee when you no longer have the time or energy to brew a pot. They are tiny, shattered Bernhardian snow globes into which to gaze and desperately shake from time to time hoping for more serpentine sentences to unfurl across the landscape, melting everything in their wake with uncompromisingly wry futility.

'So every day, when office hours are over, something intervenes, which stops me from despairing, although I should despair, although in truth I am in despair. And although I know that, because in fact I always have something after office hours which distracts me, not always something that pleases me, at least something that distracts me, I am, every time, afraid before office closing hours. Because one day, I think, it could be that I no longer have anything that gives me pleasure or even distracts me. There is simply no pleasure and no distraction any more—it's a law of nature that for every person there is, one day, no pleasure nor any distraction any more, not the least pleasure, not the most insignificant distraction...'—'Jauregg'

As far as Georg and I are concerned, we never revealed our suicide perspectives to each other, we only knew of each other that we were at home in them. We were enclosed in our thoughts of suicide as in our room and in our conduit system, as in a complicated game, comparable to advanced mathematics. In this advanced suicide game we often left each other completely in peace for weeks. We studied and thought about suicide; we read and thought about suicide; we hid away and slept and dreamed and thought about suicide. We felt abandoned in our thoughts of suicide, undisturbed; no one bothered about us. We were at liberty to kill ourselves at any time, but we did not. As much as we had always been strangers to each other, there were never any of the many hundreds of thousands of odourless human secrets between us, only the secrets of nature as such, which we knew about. Days and nights were like verses of an infinitely harmonious dark song to us.—'The Crime of an Innsbruck Shopkeeper's Son'

"His manner of speaking, like that of all the subordinated, excluded, was awkward, like a body full of wounds into which at any time anyone can strew salt, yet so insistent that it is painful to listen to it." (145)One of Bernhard's first writings jobs—in the early 1950s���was as a reporter at the courts for a Salzburg newspaper. In 1967, a collection of seven stories was published as Prosa (Prose). All of the stories in Prose are in one way or another about crime; crime, guilt, discipline, and punishment. It is a bleak collection, even by Bernardian standards, filled with cruelty and deaths and insanity and suicides. In other words, definitely worth reading, even if some of the stories are better than others.