What do you think?

Rate this book

384 pages, Hardcover

First published September 12, 2006

Only Revolutions is printed in such a way that both covers appear to be the front of the book. The side with the green cover is the story as told by Sam, and the side with the gold cover is the story as told by Hailey. Every page contains upside-down text in the bottom margin, which is actually later pages of the opposite volume. For example, the first page of Hailey's story contains the last several lines of Sam's story, apparently upside down. When you reach that page while reading Sam's story, those lines will appear to be the only right-side-up text on the page.

The first letter of each 8 page "section" is larger and bold when compared to the other letters. When the reader puts the single letters together from Hailey's side they spell out "Sam and Hailey and Sam and Hailey..." etc. When read from Sam's side, they spell out "Hailey and Sam and Hailey and Sam..." etc.

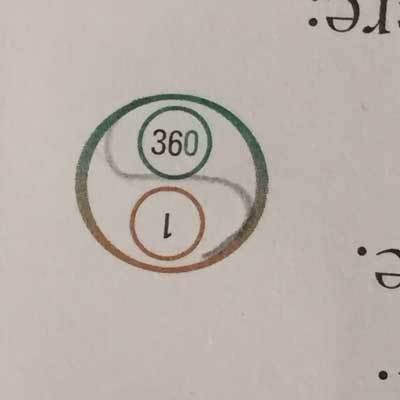

Each half-page contains exactly 90 words. When both stories are combined, the words add together for a total of 180 words per page, perhaps to symbolize the 180 degrees the reader must turn the book to read the opposite volume.[original research?:] Also, with both pages open, the full word count is 360, essentially making a revolution (360 degrees) with every open page.

The publisher recommends the reading of eight pages from one story, then the other, and so on.

In addition, every page contains a sidebar with a date and a list of world events that happened between that date and the one which appears on the next page. Dates in Sam's story run from Nov 22, 1863 to Nov 22, 1963, while dates in Hailey's story run from Nov 22, 1963 to Jan 19, 2063. This chronological sidebar, which offers a mosaic of 19th - 21st Century historical quotations, becomes blank after Only Revolutions' own publication date. The diverging point between Sam's line and Hailey's line is set at the date of the John F. Kennedy assassination, November 22, 1963.