What do you think?

Rate this book

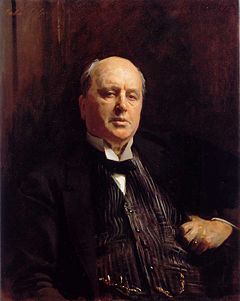

Roderick Hudson, egotistical, beautiful and an exceptionally gifted sculptor, but poor, is taken from New England to Rome by Rowland Mallet, a rich man of fine appreciative sensibilities, who intends to give Roderick the scope to develop his genius. Together they seem like twins or lovers, opposing halves of what should have been an ideal whole. Subtext : blazing unspoken sexuality.

398 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1875

"That's very true," said Roderick, serenely. "If I had not come to Rome, I wouldn't have risen, and if I had not risen, I shouldn't have fallen."

the difficulty of establishing a selective system of observation that will enable an author “to give the image and the sense of certain things while keeping them subordinate to his plan, keeping them in relation to matters more immediate and apparent, to give all the sense, in a word, without all the substance or all the surface, and so to summarise and foreshorten, so to make values both rich and sharp.

There are accidents of ruggedness in the upper portions of the Coliseum which offer a very fair imitation of the mighty excrescences in the face of an Alpine cliff. In those days a multitude of delicate flowers and sprays of wild herbage had found friendly soil in the hoary crevices, and they bloomed and nodded amid the antique masonry as naturally as if they were the boulders of a mountain.

…some sunny empty grass-grown court lost in the heart of the labyrinthine pile.

His studio was a large empty room with a vaulted ceiling, covered with vague dark traces of an old fresco which Rowland when he spent an hour with his friend used to stare at vainly for some surviving coherence of floating draperies and clasping arms.

He had fallen from a great height, but he was singularly little disfigured. The rain had spent its torrents upon him, and his clothes and hair were as wet as if billows of the ocean had flung him upon the strand. An attempt to move him would show some hideous fracture, some horrible physical dishonor, but what Rowland saw on first looking at him was only a strangely serene expression of life. The eyes were those of a dead man, but in a short time, when Rowland had closed them, the whole face seemed awake. The rain had washed away all blood; it was as if Violence, having done her work, had stolen away in shame. Roderick’s face might have shamed her; it looked admirably handsome.