What do you think?

Rate this book

297 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2010

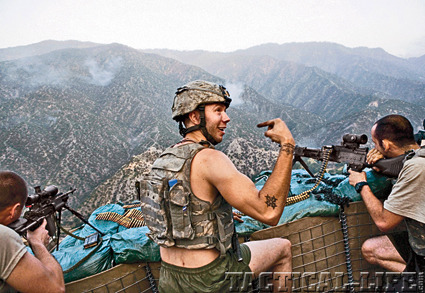

Stripped to its essence, combat is a series of quick decisions and rather precise actions carried out in concert with ten or twelve other men. In that sense it’s much more like football than, say, like a gang fight. The unit that choreographs their actions best usually wins. They might take casualties, but they win.The story here has nothing to do with politics, macro foreign policy, or terrorism, per se. Junger looks at the experience of a small band of soldiers at the front lines of the war in Afghanistan, in the eastern reaches, in a valley notorious for its peril to combatants. What matters here are the mechanisms, physical and emotional, that bind the soldiers to one another. What they consider funny, what topics are off limits, how they rely on each other, criticize each other, support each other, how they cope with or thrive on the reality of war.

The choreography—you lay down fire while I run forward, then I cover you while you move your team up—is so powerful that it can overcome enormous tactical deficits. There is a choreography for storming Omaha Beach, for taking out a pillbox bunker, and for surviving an L-shaped ambush at night on the Gatigal. The choreography always requires that each man make decisions based not on what’s best for him, but on what’s best for the group. If everyone does that, most of the group survives. If no one does, most of the group dies. That, in essence, is combat.

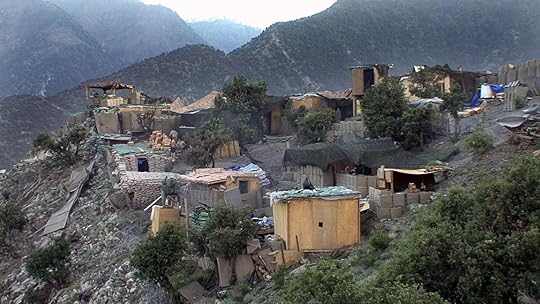

“...war came to the Korengal when timber traders from a northern faction of the Safi tribe allied themselves with the first U.S. Special Forces that came through the area in early 2002. When the Americans tried to enter the Korengal they met resistance from local timber cutters who realized that the northern Safis were poised to take over their operation... For both sides, the battle for the Korengal developed a logic of its own that sucked in more and more resources and lives until neither side could afford to walk away.”

“Moreno put his hands on him and started to pull him out of the gunfire. A Third Squad team leader named Hijar ran forward to help, and he and Moreno managed to drag Guttie behind cover before anyone got hit. By that time the medic, Doc Old, had gotten to them and was kneeling in the dirt trying to figure out how badly Guttie was hurt. Later I asked Hijar whether he had felt any hesitation before running out there. ‘No,’ Hijar said, ‘he’d do that for me. Knowing that is the only thing that makes any of this possible.’”

Wars are fought on physical terrain — deserts, mountains, etc. — as well as on what they call “human terrain.” Human terrain is essentially the social aspect of war, in all its messy and contradictory forms. The ability to navigate human terrain gives you better intelligence, better bomb-targeting data, and access to what is essentially a public relations campaign for the allegiance of the populace.