What do you think?

Rate this book

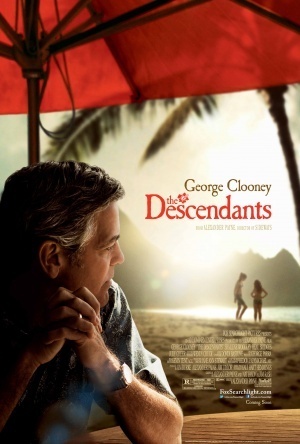

283 pages, Hardcover

First published May 15, 2007

The sun is shining, mynah birds are chattering, palm trees are swaying, so what.

I wonder if our offspring have all decided to give up. They'll never be senators or owners of a football team; they'll never be the West Coast president of NBC, the founder of Weight Watchers, the inventor of shopping carts, a prisoner of war, the number one supplier of the world's macadamia nuts. No, they'll do coke and smoke pot and take creative writing classes and laugh at us.