Peter Stothard's Blog, page 72

July 18, 2012

Motor culture

By Catharine Morris

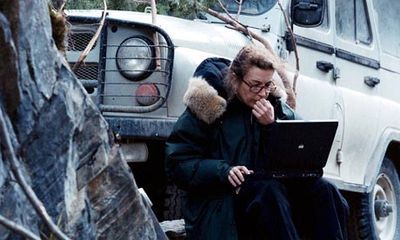

A new cultural venue opened in London last week. It’s a semi-permanent construction – part of the sixty-seven-acre King’s Cross development – and, in case you haven’t guessed it from the photograph above: it used to be a petrol station. That’s why, at its inaugural event last week, the subject under discussion was cars.

Geoff Dyer hasn't got one. He hates them. The hatred began when he was a child: his father was so mean with money that he would only buy half a tank of petrol at a time, and he was constantly having to stop to get more. Dyer was willing, nevertheless, to guide us through the history of the filling station in US art and photography – in the work of Edward Hopper, Russell Lee, Dorothea Lange and William Eggleston, for example. The loneliness and anonymity of some of the pictures were in contrast to the mood of the poem read for us by Luke Wright – inspired by his tour, in 2006, of Britain’s service stations: "Hello Moto! Welcome Break! / Massive coffee, piece of cake . . . .".

The design critic Stephen Bayley told us that he saw a Lotus XI racing car on the back of a trailer when he was about six and thought “How can a machine be so beautiful?”. He loves the drama of certain American designs – “vulgarian, non-economic and therefore fabulous”. One of the men behind these was Harley Earl. He was among the most influential designers who ever lived, Bayley said, but he never drew anything. His working method was to make a mental note of features that pleased him and then issue instructions such as “I want that line to have a duflunky, to come across, have a little hook in it, and then do a rashoom or zong . . .”.

A MoMA exhibition of 1951, “Eight Automobiles”, described cars as “rolling sculpture”. In Bayley’s view, cars don’t quite constitute art, being collective things, but they “ape the effects of art”. Part of the attraction of sports cars, he believes, lies in the “obvious erotic character” of their design and of the act of driving them, and in their military associations – he quoted a saying among American enthusiasts: “When you get in a Porsche, you feel you want to invade Poland". But cars are “ultimately about freedom, about escaping crushing tedium”, and about the imaginative journeys you go on along with the geographical ones.

Electric cars may have been W. H. Auden’s fantasy – “Dark was the day when Diesel / conceived his grim engine . . . ”; “we need . . . / an odorless and noiseless / staid little electric brougham” (from “A Curse”, 1972), but Bayley thinks that they “speak of convenience and disappointment alone”. Fortunately, there are those with something more exciting in mind. Dr Michael Jump, an aerospace engineer at Liverpool University, is working on the myCopter project, which is investigating the possibility of personal air vehicles for commuters. Jump is carrying out research using a flight simulator, working on the basis that such vehicles would have “vertical lift capability” and fly at low level.

You may be wondering how this relates to literature. Jump told us that he was inspired to enter his profession by the fiction of Arthur C. Clarke; and he stands by Clarke’s statement that “When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong”.

An artist's impression of a personal air vehicle

© Gareth Padfield; Flight Stability and Control

Top: The Filling Station, King's Cross; © John Sturrock

July 15, 2012

Amy Turner and the Spider

FROM PETER STOTHARD

A A Gill in The Sunday Times this morning pays tribute to his friend - and my friend - Amy Turner who was found hanged in her London apartment a week ago, aged 29.

Amy was a writer for The Sunday Times, on her way to becoming a great newspaper writer and maybe more than that, and, as Gill says, an extraordinary and selfless support for other writers.

A week is a short time in Sunday journalism - and because no other paper carried the news (or none that I saw) I learnt of Amy's death only today. This has been a bad day, a matter of no account except, I suspect, that it has been a bad day for many.

Amy was a friend with whom I spoke not enough - and saw sadly less. But every conversation became a memory. She was a very memorable friend.

We met when she was the assistant to the editor of The Sunday Times Magazine some five years ago. The reason was an assignment of mine that did not succeed as planned. Her job was to ensure that I repeated the route of a Latin poet's journey (c 38 BC by foot and carriage) in a vintage Alfa Romeo Spider.

It was not my own idea to follow Horace's Iter Brundisium in a tiny red sports car. But the magazine editor insisted that the Spider was essential to ensuring that readers felt the full force of Satire 1.V.

Amy fixed the car. She was also at the end of a phone when the Italian traffic police in Ariccia had taken their fifth dim view of a driving machine that lacked seatbelts, a handbrake and the means to meet Rome's non-classical emission regulations. The car had to go.

Amy knew that without the ancient Spider the new Journey to Brundisium was unlikely to find editorial favour. She was right. She organised a replacement anyway. When the trip later became a book, On the Spartacus Road, she was pleased. I was pleased that she was pleased.

Soon afterwards she became the magazine writer that she told me she had long wanted to be. She was utterly realist about our trade in modern times. She was determined not to price herself out of work. She kept hold of her old job helping other editors and writers too.

Soon after that she won wide appreciation for her pieces - and a prize. I emailed congratulations. She replied with other plans. She had a book she wanted to write. We had lunch. I cannot remember a writer more aware of the difficulties, less starry eyed about the glory.

We spoke after that from time to time - about news and stories - and I remember all those all too few times.

And now comes the news today, not strictly news but brutal and new to me.

Gill notes the grim year that this has been for journalists, for confidence and for hopes. Just as he avoids speculation about why our friend should be found hanged so do I.

I just want to remember tonight that voice in Ariccia, that lunch companion in Covent Garden and Cheltenham Spa, the journalist and writer whose future successes I had looked forward to celebrating and now will not.

July 6, 2012

French with a safety net

By J. C.

Bilingual editions of literary works, with facing-page translation, are largely the province of poetry, and are generally unsatisfactory. If your French / German / Russian is good enough to have a go, you don’t want a contrived imitation distracting your other eye. The literal summary at the foot of the page, a method pioneered by Penguin in the 1960s, is a better solution. Anvil Press has reissued Rimbaud’s Poems (£14.95) and The Complete Verse by Baudelaire (£10.95), with accurate prose versions by Oliver Bernard and Francis Scarfe, respectively. The aim is “to help readers negotiate poems without constant recourse to a dictionary”. Both collections originated in Penguin in the 1960s.

Bingual editions of prose works are rarer, but perhaps more justifiable. Julian Green’s Paris is a series of short meditations on the city in which Green was born to American parents in 1900. The facing-page translation is by J. A. Underwood. If you fancy testing your French with a safety net, or seeing how English recoils from the subjunctive, Paris, first published in 1991, offers a pleasant way of going about it. “Quoi qu’il en soit, le vieillard en question a une barbe blanche”, Green writes, to which Underwood responds, “Anyway, the old man in question had a white beard”. A few pages later, the introductory phrase is repeated: “Quoi qu’il en soit, je demeurerai toujours à ma place invisible”. This time the translator opts for “Be that as it may . . .”.

So all-absorbing is Paris that Green finds it hard to write about it while he’s there. “Sitting in the lap of the model you intend to paint has never seemed to me to be the ideal position . . . . Here, in Copenhagen, I see Paris very clearly.” The city smiles warmly on those who “flânent dans ses rues” – for which Underwood gives us “loaf in its streets”. Put away your notebook, get out a map (noting the city’s “resemblance to the human brain”) and be flâneur for a day.

The book comes with a bizarre introduction by Lila Azam Zanganeh: “Unfortunately, Mr Green, I believe you died in 1998, so you might have just missed it, but the director Woody Allen made a film . . .”. Adorned with a portfolio of Green’s photographs, Paris, published by Penguin, is priced at £11.99.

July 5, 2012

Save Our Unique Libraries

by Thea Lenarduzzi

Since, just under a year ago, we pounded the pavements (of the TLS office) to reveal how people (in the TLS office) had been nurtured by their local libraries, the threat to our institutions has not lessened. Cuts and closures have increased. Imagine, if you will, a beast of almighty height and girth, with tentacles reaching into every corner of every library and archive; add to its tentacles sharp secateurs to sever financial lifelines . . . .

The Women’s Library in East London is one of the latest to have its funding, from the London Metropolitan University, cut. Unless it is able to secure alternative funding by the end of the year, it will have to reduce its opening hours from five days a week to one. Its unique collection – which includes books (dating back to the sixteenth century), feminst magazines, pamphlets, and oddities – could be dispersed across other libraries, with limited access. (A public meeting to discuss this will take place tomorrow.)

Does a similar fate await the other libraries we have at times, perhaps, taken for granted, such as – to pluck at random – Westminster Central Music Library? Stuart Hall Library, whose visual arts collection includes more than 4,000 exhibition catalogues from around the world? Or the Saison Poetry Library on Level 5 of the Royal Festival Hall? (Their collection dates back to 1912; and I once found an unopened tube of fruit pastilles while searching for David Jones’s and Elizabeth Haines’s Sketch Book from the Somme).

These are just a few of the more unusual libraries that contribute to London’s cultural resources. But the cuts are, of course, nationwide (as this map shows: http://libraries.fromconcentrate.net/ ) and, given the “current economic climate” (etc, etc), one can only assume, worldwide. Is it time for a list of endangered libraries and, if so, which libraries should be on it?

History suggests an acronym might concentrate support. I would suggest S.O.U.L but it seems Chicago’s book lovers beat me to it with “Save Our Urban Libraries”. How about we make it “Save Our Unique Libraries” instead and join forces?

June 27, 2012

How to write in the digital age

By Catharine Morris

There have been plenty of conferences about the future of publishing, but few, if any, have been aimed at writers. The Literary Consultancy remedied this recently with a two-day conference – Writing in the Digital Age – held at the Free Word Centre in Farringdon.

One of the speakers, the American writer Robert Kroese, likened submitting a manuscript to publishers to turning up to a club to find a group of people waiting outside. Some have been there for a few minutes; others for hours. Nobody seems to know when they will be let in, if they are to be let in at all, or even what the criteria for entry are. You eventually resort to sneaking in by the back door – the back door being self-publishing, of course. Digital self-publishing.

Kroese recommends that option to those who are entrepreneurial, impatient, sociable and difficult to classify. He fits that description himself. Having done all sorts of preparatory legwork including compiling spreadsheets of potential reviewers and being funny on a blog, he uploaded his comic fantasy novel, Mercury Falls, to Amazon’s self-publishing platform in 2009. When he took the tactical step of dropping the price from $4.99 to $0.99, it made the sci-fi top twenty; and having sold 5,000 copies in its first year, it was picked up by Amazon’s flagship imprint AmazonEncore. A good number of writers have been taken on by traditional publishing houses having first had success on their own in this way. (No literary novelists among them, though, as far as we know. They still wait their turn out in the cold.)

One pressing concern was: should writers use Twitter? The answer seems to be yes, if it suits your temperament and you are in need of publicity, but don’t bang on about your book all the time – be interesting and entertaining about a range of topics and then casually mention it as if in passing.

Writers can bring their personalities to bear on Facebook too; those who keep a private account can also use it, Linda Grant told us, as a literary salon and somewhere to “talk about problems with writing . . . the day-to-day vicissitudes”; one author she knows posted an account of a two-hour book signing during which he sold one book, whereupon “everyone piled in with similar experiences”. Kate Mosse pointed out that, amid all the social networking (which she herself shuns), you have to write the novel. If Facebook and Twitter start to eat into your writing time you can always – Grant’s suggestion – buy software that disables them until you reboot your computer.

The keynote speaker, the novelist Hari Kunzru, addressed the wider implications of living in a data-rich, technologically advanced era. Is the novel an outdated form? We live in a time of unprecedented change, he said; our lives are characterized by participation in networks, and literary fiction is particularly good at representing them. More than that, there is interest to be drawn from new forms of language – the language of text messages, online advertising, instant messaging and spam. (Kunzru collects examples of that modern epistolary form, the financial scam letter.)

But our era also “raises questions about authorship”. Kunzru told us about prose and poetry “written” by a computer, and about a spam Twitter account called @horse_ebooks whose tweets – fragments from a range of texts, including advertising material, with occasional links – sometimes have a striking “oratorical tone”. What does it mean if we can experience machine-generated text as literature?, he asked. It's a difficult question to answer, but perhaps it's worth posing: when I last checked, @horse_ebooks had 80,873 followers.

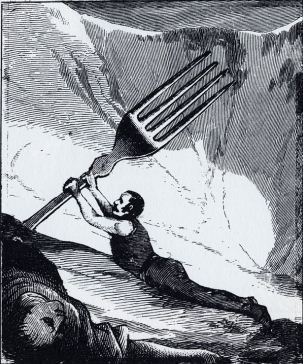

Illustrations by Joan Hall, from The Policeman's Beard Is Half Constructed: Computer prose and poetry by Racter (1984; Warner Software/Warner Books)

June 21, 2012

Into cleanness leaping

by Adrian Tahourdin

The London Olympics, as we know all too well, are just over a month away. In common with most people who tried to get tickets I was almost entirely unsuccessful: I have one set of tickets for a fencing session, which will be a new experience. I’m not sure quite what to expect.

I was rather hoping — and expecting — to see some cycling and, more especially, a few swimming heats in Zaha Hadid’s spanking new Aquatics Centre — I even took the precaution of applying for tickets to the early rounds as I assumed they’d be less sought after. No such luck.

But I’ve consoled myself with the thought that swimming is weirdly effective as a televised sport: the drama of the race is all the more intense for being indoors and in the water. Add to that the fantastic camerawork and the rapid turnover of heats and you have quite a spectacle. Can anyone who saw it forget Rebecca Adlington’s spectacular 800 metre powerdrive in the Beijing Olympics of 2008? Or Michael Phelps’s eight golds, including one when, he revealed afterwards, his goggles were letting in water and he couldn’t even see properly. Great things are expected of both again. Ian Thorpe (“Thorpedo”) hasn’t made the Australian team, which is a shame as it would have been fun to see him renew his rivalry with Phelps. Thorpe’s stroke was a thing of beauty, swimming elevated to an art form.

What will be the Olympic legacy (dread phrase) in the aquatic sphere? New Olympic-style 50m pools being built around the country? Hardly likely in the current economic climate. Our leisure centres are fine and quite impressive in a way but . . . . On a trip to Toulouse a few years ago I counted six 50 m pools in the city, including a beautiful outdoor one. Toulouse is only France’s fifth largest city; London can only dream of such riches, although it does boast the magnificent Tooting Bec lido (91 metres — why 91?).

But maybe the British don’t need, or especially appreciate, the regimentation of lanes, lifeguards, no-diving notices etc. Books such as the late Roger Deakin’s wonderfully eccentric Waterlog are eloquent testimony to a native ability to find bathing opportunities in unlikely places — not all of them authorized I’m sure. Deakin is the kind of swimmer who could have found a stagnant pond somehow appealing.

To be ranked alongside Deakin’s swimming memoir is Charles Sprawson’s Haunts of the Black Masseur: The swimmer as hero, a rich literary and cultural history of the aquatic sport. Byron, an early conqueror of the Hellespont (a feat in which he has been followed by Sprawson himself) is given due prominence, along with other reckless and brave swimmers such as Byron’s friend Edward John Trelawny, and of course Swinburne. Sprawson reminds us of Goethe’s love affair with water. Did this help to spark a German passion for aquatic sports?

The American broadcast journalist Lynn Sherr has just produced a breezy and informative book, Swim: Why we love the water. Sherr is another successful Hellespont swimmer, a feat she describes in triumphant detail. John Cheever’s “The Swimmer” (“The day was beautiful and it seemed to him that a long swim might enlarge and celebrate its beauty”) gets a section; Sherr reminds us that Burt Lancaster needed swimming lessons in order to perform the title role in the film. Presumably he couldn’t swim when From Here to Eternity was filmed some 15 years earlier.

Among swimming US Presidents, Sherr tells us that Theodore Roosevelt “skinny-dipped in the Potomac” while the athletic Gerald Ford “commissioned the outdoor pool at the White House”. Reagan had been a lifeguard. “In 1933, a White House laundry room was converted into a swimming pool so that the polio-stricken president Franklin Delano Roosevelt could get some exercise. President John F. Kennedy used it for noontime naked swims, partly to relieve his chronic back problems. In 1969, it was bricked over by President Richard Nixon (once photographed walking the beach in shoes and socks) to make, ironically, a press room.“

Sherr’s enthusiasm is infectious, even if she does seem to think Coleridge helped to launch the Romantic movement in 1886. In her bibliography she lists an intriguing-sounding publication, Traité complet de natation: Essai sur son application à l’art de la guerre (1835), by M le vicomte de Courtivron. I must track that one down.

Another book that shouldn't be overlooked is Kate Rew's handsome Wild Swim: River, lake, lido and sea: the best places to swim outdoors in Britain. Usefully divided up by county and full of wonderful photographs, it should be on every amateur swimmer’s shelf. Apart from anything else, it was a singularly magnanimous gesture on the author’s part to reveal so many hitherto unknown spots for swimming. I take guilty (and rather selfish) pleasure from the fact that my own favourite swimming place is absent from the book.

June 8, 2012

Breakfast with Betjeman, sherry with Waugh

By Thea Lenarduzzi

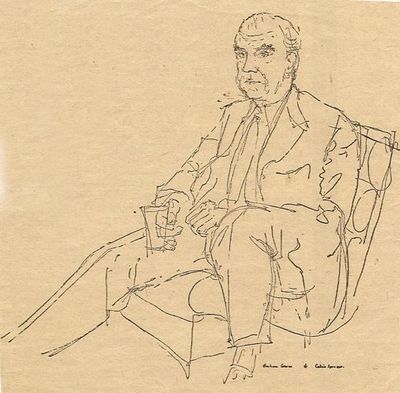

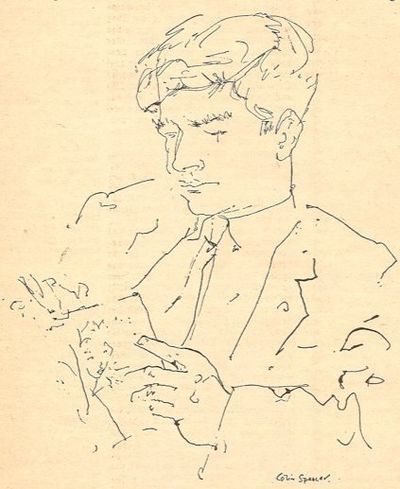

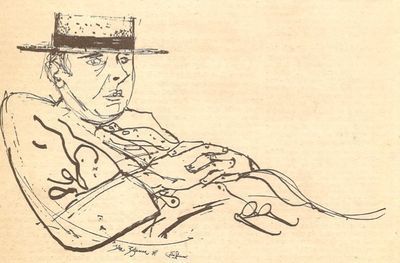

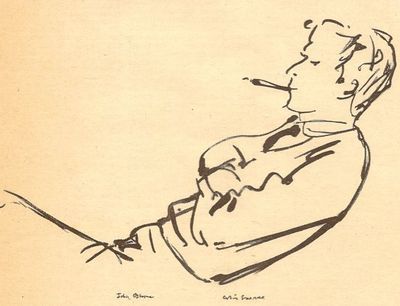

The TLS tends to be associated more with words than pictures (which is not to say that the artwork is not fantastic – just look at this week’s cover). But it has been a while, perhaps, since pictures took centre stage as they did (or should have done) for a brief period in 1959, when the editor Alan Pryce-Jones commissioned a series of drawings called Writers of Our Time.

Colin Spencer, whose portraits of E. M. Forster and John Betjeman on the cover of the London Magazine had caught Pryce-Jones’s eye, was to travel to the homes, clubs or offices of the twenty-five writers in question and capture them in their element. Among them were W. H. Auden, J. B. Priestley, Rebecca West and Stevie Smith, as well as the younger V. S. Naipaul and Iris Murdoch.

Some were more difficult to pin down than others. T. S. Eliot, for example, was impossibly busy (he had, to be fair, just accepted a commission from the Archbishop of Canterbury to produce The Revised Psalter) – but it was, perhaps, more because he disagreed with the TLS printing drawings at all.

Fortunately, others were more forthcoming. Betjeman liked to meet Spencer for breakfast at his flat near Smithfield, after which the drawing could begin. John Osborne, who was in the middle of rehearsals for his musical satire of the critics and the popular press The World of Paul Slickey (due a revival, surely?), took advantage of a lull in the music for a cigarette and a striking profile pose:

(Would but these sitters had reclined together in reality as above – what a dream meeting that would have made for.…)

Graham Greene, meanwhile, sipped his drink (tea?), and Naipaul leafed through a magazine in a shabby Streatham flat:

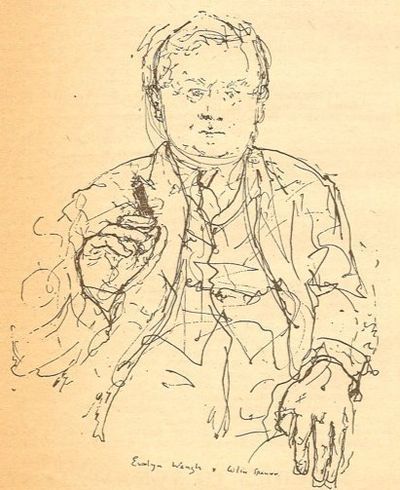

Evelyn Waugh lived in the less humble surroundings of Combe Florey, a large manor on the outskirts of Taunton. Taking the 9:30 train from Paddington as per Waugh’s strict instructions, Spencer was greeted on the platform by Mrs and Mrs Waugh “as if I was the children’s tutor”. A rich lunch – fish in a cream sauce; silver-service all the way – and numerous sherries later, Waugh was more candid: “You’ll notice that I have a small face inside a larger one . . . . It’s the result of fat, it grows rings around you”. He subsequently fell asleep, enabling Spencer to sketch a couple of him unawares and smuggle them out in his pad.

(“He looked like a podgy, spoilt child”, recalls Spencer of this version, which was Waugh's favourite.)

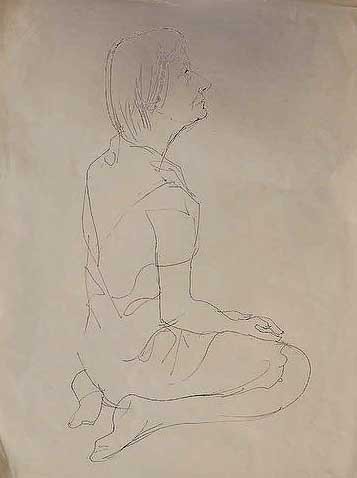

A number of the portraits did not make it into print. Pryce-Jones accepted a position as an adviser to the Ford Foundation in New York, leaving Arthur Crooke to take over the editorship towards the end of 1959. Perhaps Crooke agreed with Eliot and plumped for more words instead; Spencer’s drawings of Stevie Smith, for example, never appeared in the TLS, but here is one, by way of atonement.

(All pictures are courtesy of the artist, Colin Spencer http://colinspencer.co.uk/home.html)

May 25, 2012

Wait a minute Mr Postman

by Thea Lenarduzzi

Ever since my nineteenth birthday card from my Aunty Marie failed to arrive, along with the enclosed £10 note, I have had an uneasy relationship with the postal service. But letters are a source of other forms of riches too, as the Post Office in Pictures exhibition, organized by the British Postal Museum and Archive (BPMA), at the beautiful Lumen URC reminds us.

The images on display, drawn mainly from the Post Office Magazine and Courier, document postal history from the 1930s onwards, focusing on the people that take our letters from A to B, come hell or high water – as this image of a mail cart bound for Holy Island in 1938 demonstrates:

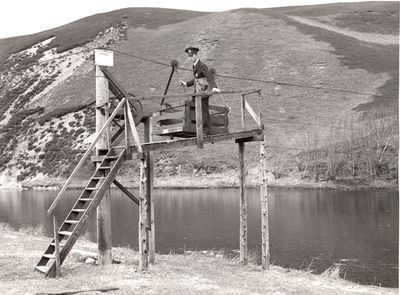

The “Bucket Bridge” (below), used to cross the River Findhorn in northern Scotland between 1939 and 1960, shows no small initiative.

These workers could only dream of the regulated efficiency of sending a letter from Barchester to Framley in Anthony Trollope’s fictional county of Barsetshire:

“… for that letter went into Barchester by the Courcy night mail-cart, which, on its road, passes through the villages of Uffey and Chaldicotes, reaching Barchester in time for the up mail-train from London. By that train, the letter was sent towards the metropolis as far as the junction of the Barset branch line, but there it was turned in its course, and came down again by the main line as far as Silverbridge; at which place, between six and seven in the morning, it was shouldered by the Framley footpost messenger, and in due course delivered at the Framley Parsonage exactly as Mrs Robarts had finished reading prayers to the four servants. Or, I should say rather, that such would in its usual course have been that letter’s destiny. As it was, however, it reached Silverbridge on Sunday, and lay there till the Monday, as the Framley people have declined their Sunday post. And then again, when the letter was delivered at the parsonage, on that wet Monday morning, Mrs Robarts was not at home.”

(What might have happened had these parcels required a signature is anyone’s guess.)

Trollope is one of the Post Office’s more high-profile employees. The Office provided material for his novels, from his early “hobbledehoyhood” working as a clerk on a salary of only £90 a year, to his appointment in 1859, after twenty-five years’s service, to the post of Surveyor of the Eastern District of England, with a salary of £700.

This is not to mention the role played by the postal service in the development of the epistolary novel. We can only wonder whether, without reliable deliveries, the genre could have reached such prominence as it did in the eighteenth century. What of Dracula and Frankenstein, were it not for the anonymous postman – or, transnational as the correspondences were, postmen – who carried the plot forward in their mail sacks? One feels emails might have quelled the suspense somewhat, and Captain Robert Walton’s mobile phone would certainly not have had signal in the North Pole.

Set this service to a tune and you get the Solent Male Voice Choir, formed in 1961 by a troupe of postmen who found, while sorting letters and parcels, musical inspiration. They will be performing as part of the exhibition, at Lumen on Saturday, August 18, at 7pm.

Perhaps, considering everything the postal service has done over the years, I might finally let that £10 slide.

(All pictures are courtesy of the Royal Mail Group Ltd / The British Postal Museum & Archive.)

May 23, 2012

Beautiful imperfection - Marie Colvin and Cerys Matthews

By Alan Jenkins

Shortly after Marie Colvin was killed in Homs the Sunday Times called me and asked if I would be trying to write anything for or about her. No, no, I protested, it was far too soon, too early even for grief; I was in shock. In the small hours of that night I woke with a start of deep shame at what Marie would have thought of my maidenly blushes. Over the next few days and nights I wrote a poem I called “Reports of My Survival May be Exaggerated” – Marie’s words on a Facebook update posted a day or so before her death, when, having filed her ST report from Babr Amr and got safely out, she decided to go back in, to witness the next stage of Assad’s war on his own people. Reporting wars was, after all, what she did. Writing poems is, after all, what I am supposed to do.

Though not herself an artist, Marie sought perfection of the work and not the life – a perfection as unattainable in our world as it is in hers. And imperfection, as if we needed reminding, is always waiting to ambush us. The poem was printed as part of the ST’s handsome tribute to Marie, the weekend after she died. It was word-perfect – that is, the text appeared just as I had submitted it. Soon after, a friend of Marie’s and mine, commiserating with me on our loss, added his regret at the misprint in one of the poem’s lines: “Rie, get up off that bloodstained floor!”. “Rie” should surely have read “Rise”, no? No no, I protested again, “Rie” (pronounced Ree) was my affectionate abbreviation of Marie, what I had in fact called her for most of our twenty-five-year friendship. When it was reprinted in the Order of Service for Marie’s London funeral, I altered the line to read “Marie, get up off…” etc. Next was another request from the ST, this time to read the poem at her memorial service. No maidenly blushes now, weeks after the event and the funeral. Again, the poem was printed in the Order of Service. This time the same line read “Marie, get off that bloodstained floor”. As I read I was careful to revert to the original.

That memorable service included beautiful renditions by Cerys Matthews of “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Crazy”, the Willie Nelson song made famous by Patsy Cline – both Marie’s public and private faces thus unforgettably present. A few days later, another call from the ST. Cerys had liked the poem and hoped she might read it herself, in the poetry slot on her radio show. Of course, that would be wonderful – only, one thing, could she please be asked to make sure she read “…get UP off that bloodstained floor”? – As, when the time came, she did. A moment later she also read my line (in the poem, spoken by Marie herself) “Can’t you take in that I am dead?”, “Can’t you take IT in that I am dead?”: correct, perhaps, strictly speaking, and even idiomatically speaking. But Marie’s American-English idiom included lots of little departures from correctness, especially when she was tired and/or emotional, and it was this I had somehow meant to suggest. There was the metrical issue too… Then came the line, “In Chechnya or Chiswick Eyot” – Chiswick Eyot being the little island in the Thames a few yards from Marie’s house, Eyot an alternative spelling of ait and in the poem rhymed with “hate”. Cerys: “In Chechnya or Chiswick EYE-ott”. Does it matter? Probably not. The whole thing sounds fragile and haunted beyond anything I had dared to hope or expect, and Marie would have loved every second of it.

Listen to Cerys Matthews reading "Reports of My Survival May be Exaggerated" (at around 1h39), available until May 26th http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio/player/b01hz3tm

‘REPORTS OF MY SURVIVAL MAY BE EXAGGERATED’

(Marie Colvin, February 20th 2012)

How can you be lying there?

Immodestly, among the rubble

When we want you to be here

In some other kind of trouble –

Luffing up, in irons, perhaps,

Just downstream from the Dove,

Lost in South London, without maps,

Or capsized in love.

What’s keeping you? A kind of dare?

Come back and tell us how you stayed

One step ahead, how you gave fear

The slip, how you were not afraid –

As we are. Look – here’s my idea.

Come back – this time, for good.

Leave your flak jacket and your gear

In that burnt-out neighbourhood,

And fly home, via Paris. You’ll be met.

I’ll buy a bottle from the corner store,

Like old times. You can have a cigarette.

Marie, get up off that bloodstained floor!

****

Tonight you threw your thin brown arm

Around my shoulders, and you said

(There was this unearthly calm)

‘Can’t you take in that I am dead?

Learn to expect the unexpected turn

Of the tide, the unmarked reef,

The rock that should be off the stern

On which we come to grief?

The lies, the ignorance and hate –

The bigger picture? No safe mooring there,

In Chechnya or Chiswick Eyot.

Those nights I drank my way out of despair,

And filling ashtrays filed the copy

You would read – or not read – with

A brackish taste and your first coffee

Contending on your tongue; while Billy Smith,

My street cat rescued from Jerusalem,

Barged in, shouting, from his wars….

As many lives as his – and now I’ve used them.

I wish I’d made it back to yours.’

May 17, 2012

How to have style

By J. C.

We’re all writers nowadays, living in the era of the blog, the age of anti-elitism, the epoch of self-publishing. Editors at mainstream houses do many things, but editing isn’t always one of them. And yet, and yet . . . a line divides the good writer from the late-night assailant of the defenceless keyboard. To put it another way, what separates writers from people who write is style. A good start in the cultivation of a style would be to avoid phrases such as “and yet, and yet”.

There are many guides to writing well. The best emphasize the writer’s duty to serve the language. F. L. Lucas was mindful of this and the parallel objective of serving the reader. In Style: The art of writing well, first published in 1955, Lucas grouped a clutch of chapters around the heading “Courtesy to Readers”. The first courtesy is Clarity, the second Brevity, the third Urbanity. A subsequent chapter begins: “No manual of style that I know of has a word to say of good humour; and yet, for me, a lack of it can sometimes blemish all the literary beauties and blandishments ever taught”.

Both humour and courtesy are illustrated by an anecdote involving Alfred de Vigny. After his reception into the Académie française, he asked a friend for an opinion on the speech he had just delivered. “Superb, though perhaps a little long”, hazarded the tactful fellow. Vigny hastened to reassure him. “Not at all. I don’t feel the least bit tired."

Lucas attributed his liking for concision to his wartime work in intelligence at Bletchley Park. “Too many books are large simply from lack of patience – it would have taken too long to make them short.” He preferred “the brevity of strength and restraint” to the fecundity of “vigorous genius” found in Balzac and Walter Scott, but was happy to add that “brevity, like clarity, has its limitations . . . . It is not good to feed horses on nothing but oats”. As for Lucas’s own style, a comment on a passage from Jeremy Bentham’s Fragment on Government gives an idea of what to expect: “Much as I loathe that ubiquitous pismire of a word – ‘the’, Bentham’s omissions of it here too much suggest a telegram”. Style, which began life as a series of lectures at Cambridge, is reissued by Harriman House of Petersfield, Hampshire, at £14.99.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers