Voynich Reconsidered: Domesday

In an earlier article on this platform, I reported on my ongoing search for a machine-readable text in abbreviated Latin. Such a text, of sufficient length, would permit a statistical comparison with the Voynich manuscript, and thereby an objective evaluation of abbreviated Latin as a precursor language.

I found another candidate document, in the form of the complete Domesday Book, in the 1783 edition, which also transcribes the original manuscript into a modern typeface (I think, Record font). The edition is available from https://archive.org/details/gri_33125... and can be downloaded as a single pdf file of 780 pages.

The Domesday Book, being essentially a census of lands and properties in England, is a highly repetitive text. It occurred to me therefore that a short extract might be representative, in statistical terms, of the whole volume. To this end, as an experiment, I randomly selected page 119, which covers a number of farms and villages in the county of Hampshire. After applying optical character recognition and cleaning up the errors, I had a text file with 512 “words” (including single-letter abbreviations) and 1,727 characters.

Below is an extract from the original manuscript, with the corresponding transcription from 1783 and my OCR output for comparison.

Three versions of an extract from the Domesday Book. (Left) from the original manuscript, probably written in 1087; (middle) from the printed transcription published by Abraham Farley in 1783, page 119; (right) my transcription in Unicode symbols. Image credits: public domain and author's work. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pQtUUF

Even on such a small sample, some statistical tests seemed worthwhile. The average “word” length was 2.86 characters, compared to 3.78 glyphs in my v101④ transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. If the Voynich text had precursor documents in abbreviated Latin, the Domesday Book is even more radically abbreviated. The vocabulary is highly condensed: just 137 “words”, of which 40 are abbreviations. The top ten “words” account for 31 percent of the “word” count.

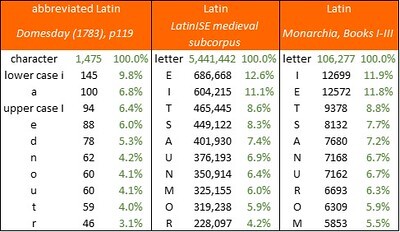

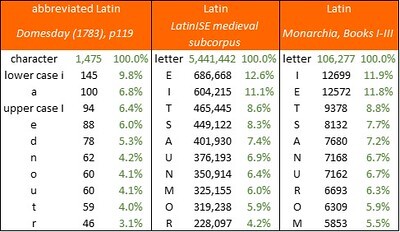

Running this sample through the Browserling character counter yielded the frequency distribution, which I could then compare with those in conventional corpora of unabbreviated Latin. An extract from the results is below. As with Exon Domesday, the character frequencies do not closely match up with those in the LatinISE medieval subcorpus or in Monarchia.

The top ten characters in the "Domesday Book", 1783 edition, page 119; and for comparison, the top ten letters in the LatinISE medieval subcorpus and in Dante's "Monarchia". Author's analysis.

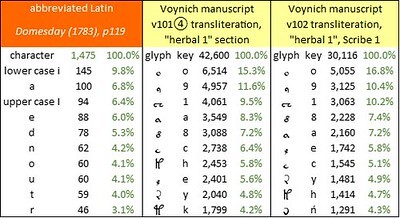

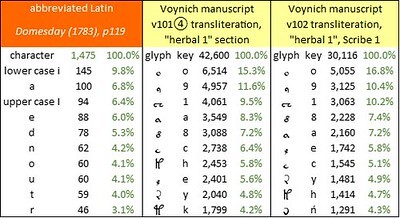

I ventured one more test, without any expectation of statistical significance. This was to compare the Domesday sample with the glyph frequencies in my various transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. In this test, the following transliterations had the best statistical fit with Domesday:

The top ten characters in the "Domesday Book", 1783 edition, page 119; and for comparison, the top ten glyphs in my v101④ and v102 transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis.

These statistical results are not brilliant. I would not propose to attach much significance to them, pending development of a much larger sample of text in abbreviated Latin; and ideally, a sample much closer in time to the fifteenth century.

I found another candidate document, in the form of the complete Domesday Book, in the 1783 edition, which also transcribes the original manuscript into a modern typeface (I think, Record font). The edition is available from https://archive.org/details/gri_33125... and can be downloaded as a single pdf file of 780 pages.

The Domesday Book, being essentially a census of lands and properties in England, is a highly repetitive text. It occurred to me therefore that a short extract might be representative, in statistical terms, of the whole volume. To this end, as an experiment, I randomly selected page 119, which covers a number of farms and villages in the county of Hampshire. After applying optical character recognition and cleaning up the errors, I had a text file with 512 “words” (including single-letter abbreviations) and 1,727 characters.

Below is an extract from the original manuscript, with the corresponding transcription from 1783 and my OCR output for comparison.

Three versions of an extract from the Domesday Book. (Left) from the original manuscript, probably written in 1087; (middle) from the printed transcription published by Abraham Farley in 1783, page 119; (right) my transcription in Unicode symbols. Image credits: public domain and author's work. Higher resolution at https://flic.kr/p/2pQtUUF

Even on such a small sample, some statistical tests seemed worthwhile. The average “word” length was 2.86 characters, compared to 3.78 glyphs in my v101④ transliteration of the Voynich manuscript. If the Voynich text had precursor documents in abbreviated Latin, the Domesday Book is even more radically abbreviated. The vocabulary is highly condensed: just 137 “words”, of which 40 are abbreviations. The top ten “words” account for 31 percent of the “word” count.

Running this sample through the Browserling character counter yielded the frequency distribution, which I could then compare with those in conventional corpora of unabbreviated Latin. An extract from the results is below. As with Exon Domesday, the character frequencies do not closely match up with those in the LatinISE medieval subcorpus or in Monarchia.

The top ten characters in the "Domesday Book", 1783 edition, page 119; and for comparison, the top ten letters in the LatinISE medieval subcorpus and in Dante's "Monarchia". Author's analysis.

I ventured one more test, without any expectation of statistical significance. This was to compare the Domesday sample with the glyph frequencies in my various transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. In this test, the following transliterations had the best statistical fit with Domesday:

• v101④, that is, Glen Claston’s v101 with all occurrences of {4o} replaced by the Unicode symbol ④; "herbal" sectionA juxtaposition of the most frequent Domesday characters and the most frequent Voynich glyphs is presented below.

- average absolute difference between glyph frequencies and character frequencies: 0.77 percent

• v102, that is, v101④ with merging of various groups of visually similar glyphs; "herbal" section, Scribe 1

- correlation between glyph frequencies and character frequencies: 97.7 percent.

The top ten characters in the "Domesday Book", 1783 edition, page 119; and for comparison, the top ten glyphs in my v101④ and v102 transliterations of the Voynich manuscript. Author's analysis.

These statistical results are not brilliant. I would not propose to attach much significance to them, pending development of a much larger sample of text in abbreviated Latin; and ideally, a sample much closer in time to the fifteenth century.

Published on May 11, 2024 09:40

•

Tags:

abraham-farley, domesday, exon-domesday, voynich

No comments have been added yet.

Great 20th century mysteries

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pe

In this platform on GoodReads/Amazon, I am assembling some of the backstories to my research for D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 (Schiffer Books, 2021), Mallory, Irvine, Everest: The Last Step But One (Pen And Sword Books, April 2024), Voynich Reconsidered (Schiffer Books, August 2024), and D. B. Cooper and Flight 305 Revisited (Schiffer Books, coming in 2026),

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

These articles are also an expression of my gratitude to Schiffer and to Pen And Sword, for their investment in the design and production of these books.

Every word on this blog is written by me. Nothing is generated by so-called "artificial intelligence": which is certainly artificial but is not intelligence. ...more

- Robert H. Edwards's profile

- 68 followers