What do you think?

Rate this book

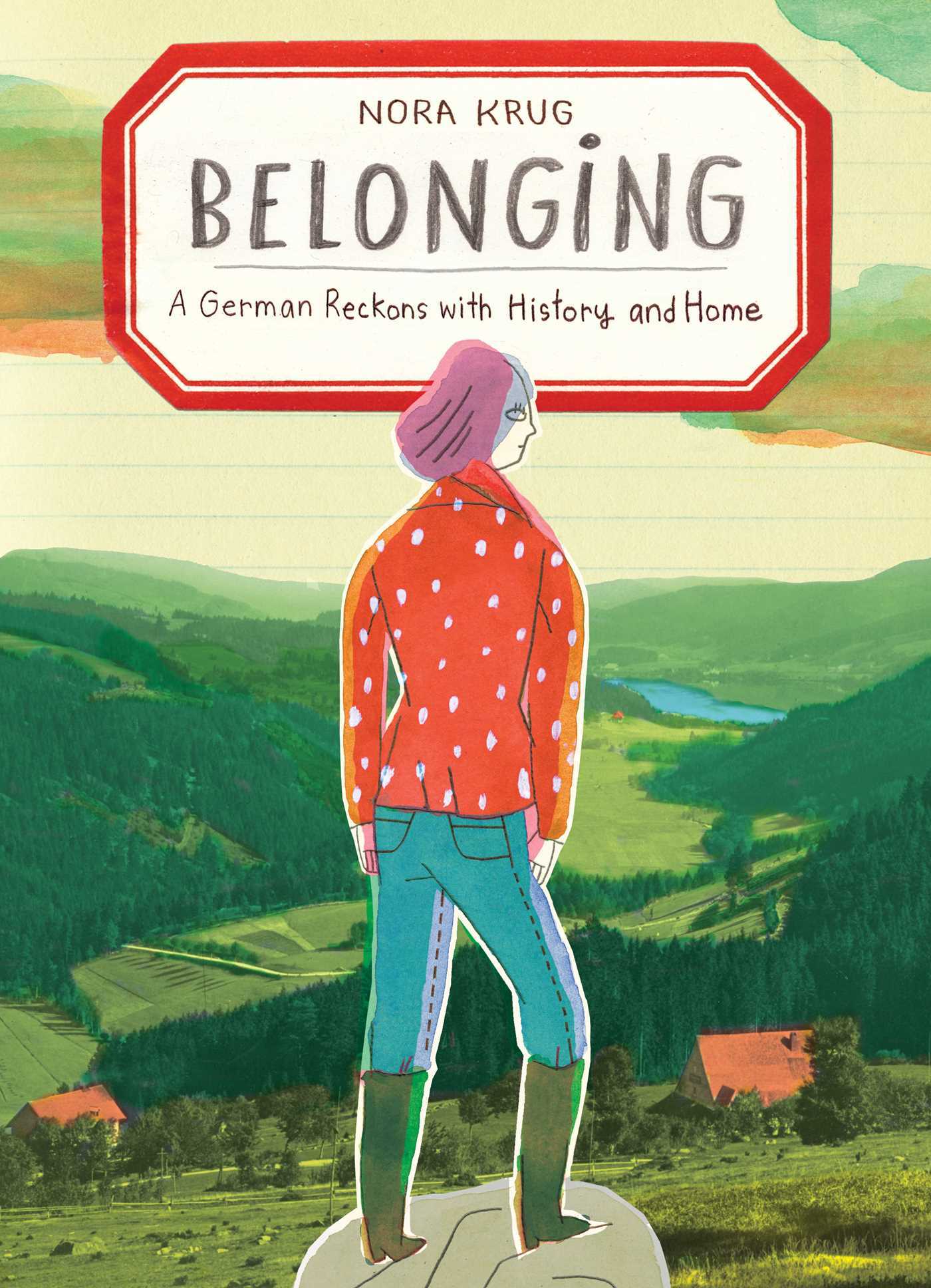

288 pages, Hardcover

First published August 27, 2018

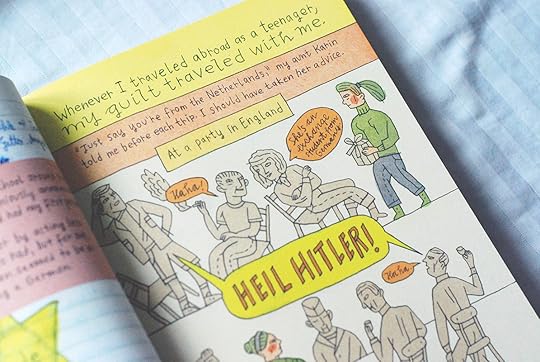

I slowly began to accept that my knowledge will have limits, that I’ll never know exactly what Willi thought, what he saw or heard, what he decided to do or not to do, what he could have done and failed to do, and why.