What do you think?

Rate this book

770 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2009

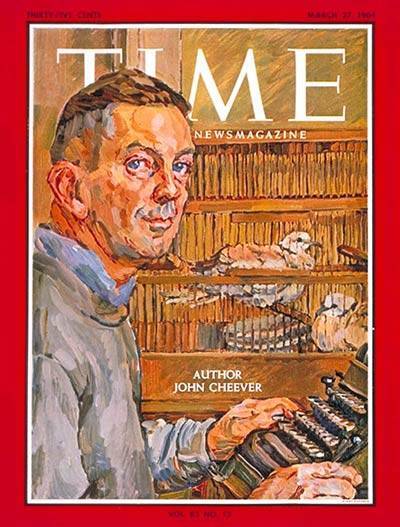

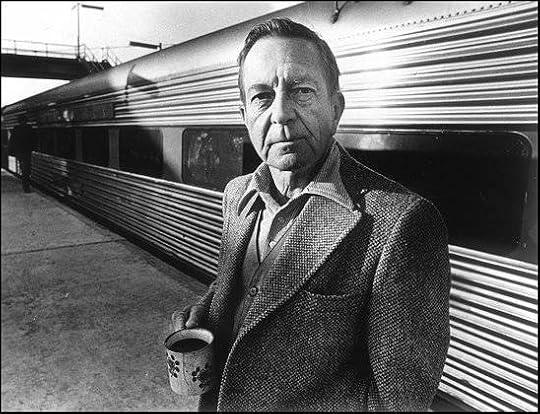

Most critics felt that Blake Bailey's book was an admirable work of scholarship and approved of his task of encouraging people to read Cheever again. But they disagreed about the extent to which Cheever succeeds as a literary biography. A few reviewers thought that Bailey had done an incomparable job of integrating the details of the man's life with his work. Others, however, opined that the book's exhaustive detail gives readers almost no insight into Cheever the author. Most assessments were more balanced, noting that while Bailey's research was very thorough, the reason we're ultimately interested in this man is due to his fiction, not his failings.

This is an excerpt from a review published in Bookmarks magazine.