What do you think?

Rate this book

112 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2010

It is his voice that haunts me, cataloguing every trivial detail of the world and fretting about them. The master's mapping of nature doesn't amount to anything, it only steeps the world in doubt and hesitation and tedious references to other authors' doubts and hesitations.- Pliny the Elder's scribe and slave Diocles gives his opinion about the "Naturalis Historia".

Lolli Editions is an independent publisher based at Somerset House in London. We publish radical and formally innovative fiction that challenges existing ideas and breathes new life into the novel form. Our aim is to introduce to the Anglophone world some of the most exciting writers that speak to our shared culture in new and compelling ways, from Europe and beyond.

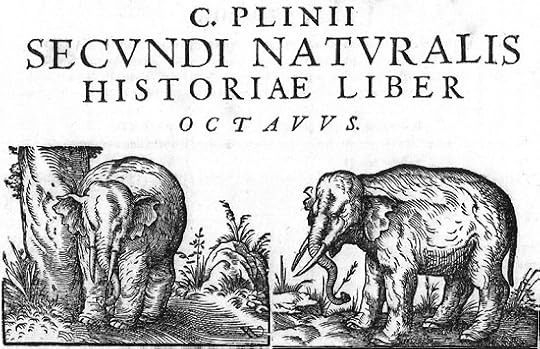

Awake began as a nightmare, the kind that lingers in the body for a while. The nightmare was not about Pliny the Elder, but the book turned out to be. He wrote an encyclopedia, Naturalis Historia, which was an effort to master nature through knowledge and the magic inherent in the naming of each of nature’s parts. His curiosity is well mixed with hate, self-pity, fear of the feminine and lust for power – in a sense characteristic of the Western history of ideas, although here taken to a rarely seen extreme. We talk about nature differently now, but a lot of us still live by Pliny’s manual. He would be proud of us and it seems fitting to let him speak again now that we have come so far with nature’s destruction.

Pliny the Elder

I am lying on my stomach on a blanket outside the villa, baking under the sun. My sister's boy, little Gaius, is wobbling around me. He is making a speech he has prepared, in which he appeals to Lucretia not to take her own life after her rape by Tarquinius. I am lying here sweating, listening to a child tackle the elastics of guilt. It is partly comforting and partly alarming to hear him weigh the notion as deftly as any lawyer in the Forum. He is already indifferent. I can no longer feel the border between my body and the world, the hot blanket, the warm air. When I lie here, eyes closed, I feel borderless. The birds sing in me, the boy, with his hypocrite talk and theatrical gesticulation, walks in me. The tall plane tree, thronged by cicadas, snaps and hisses. I lie in the sun with my eyes closed, watching the illuminated insides of my lids. Warm red. In Germania, I saw a king sacrifice a bull to his gods. The bull's blood was collected in a silver basin on an altar of turf. When the basin was full, the king placed a thin wooden disc on the surface. A face had been cut into each side of the disc. One was angry and warlike, the other was laughing, tongue snaking from the open mouth. The disc, its laughing face up, trembled in the steaming blood. Then the king placed the bull's testicles on the disc, which sank under their weight and then popped back up, now with the angry war face on top. An omen, I believe. I feel like that laughing face now as it turned towards the bottom. [107–8]

Nature created man solely so he could suffer, the only animal who cries, the only animal who knows death and understands the scope of its suffering. The only animal who understands that it is made to suffer for nature’s amusement. He who believes himself meant for bigger things is the unknowing victim of nature’s game, hardly better than an animal. My suggestion: we must learn to enjoy the cruel game, and so be it that it is at our own expense.