What do you think?

Rate this book

151 pages, Paperback

First published November 9, 2017

“I’m writing a book about Farenheit 451” I explained the ruckus with the estate. The end of borders.

[He] looked uncomfortable “Sounds a bit meta” he said

“Yes it is a bit meta” I reached up and touch my face, cheek burning. Time for another apology. “That’s the last thing we need” I said

My homage to Fahrenheit 451 was going to be a searing feminist rewrite of Bradbury’s classic, like Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, only blonder.Megan Dunn’s first book, Tinderbox, is another excellent publication from Galley Beggar Press, one of the UK's most exciting small independent presses, best known for publishing A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, but also responsible in 2017 for perhaps the most original book I read this year, Forbidden Line and the wonderful King Lear take We That Are Young, which recognised by the Republic of Consciousness Prize.

It is about the end of the Borders book chain, Julie Christie and me – but not necessarily in that order.After a seven-year stint with Borders UK, Dunn was still there in 2009 when the chain was put into voluntary administration, perhaps killed by the Kindle (although as Dunn later notes, rival chain Waterstones survives to this day):

It is also about Ray Bradbury, censorship and the end of the world – but not necessarily in that order.

It is also about Jeff intellectual, Bezos freedom, and Piggle Iggle – not in order but that necessarily.

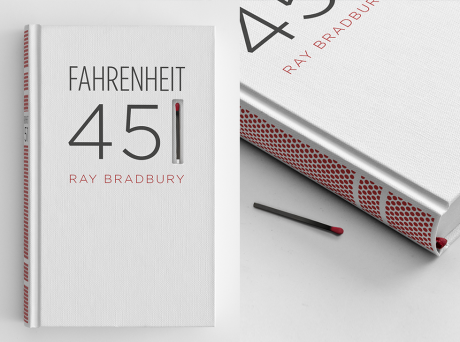

I’d started thinking about Fahrenheit 451 during those last critical months when I was the sales manager at Borders Kingston-Upon Thames. In the wake of Amazon’s Kindle it seemed unlikely that books would ever be banned: instead books are commodified, turned into movies and TV series, rated and recommended in Goodreads, their individual sales histories quantified on Nielsen Bookdata and in the fathomless depths of the Amazon Sales Ranking system. Even the Kindle was named by a branding consultant who suggested the word to Amazon because it means to light a fire. The branding consultant thought that ‘kindle’ was an apt metaphor for reading and intellectual excitement.Returning to her native New Zealand, she joins in with National Novel Writing Month ('NaNoWriMo') and starts to write her first novel, intended to be a re-write of Fahrenheit 451.

Clarisse and Montag isn’t meant to be sexual, but she’s a teenager and he’s a married man. And she also twirls a dandelion under his chin and asks him if he’s happy. Then she tells him to taste the rain. I snorted. It was pretty forward stuff for the 1950s. I wouldn’t twirl a dandelion under a fireman’s chin now. Let alone ask a married man to open his mouth and let the rain in.And she tries to re-imagine the story from their perspectives. Excerpts of her proto-novel are included, in italics, in the text:

[…]

Truffaut had cast the actress Julie Christie as both Mildred and Clarisse. Christie was British. Bradbury was not happy about this decision because Clarisse was meant to be a schoolgirl. Not a blonde bombshell from the swinging sixties who was in her mid-twenties. The age change didn’t bother me. I liked Julie Christie. She looked especially hot as Montag’s wife, wearing a long silken wig with bangs.

I bet Clarisse had a crush on Montag. Crush. A short rush mounted by that high C.But she finds it hard to write against the tyranny of the daily wordcount monitor of the NaNoWriMo, and hard to move the narrative from her own experiences:

The rain fell systematically on the domed roof of the school, like data collating, reacting, endlessly responding.‘This used to be my high school. But it’s changed. When I was here the building was wooden. Of course we would never use the world’s natural resources so carelessly now. When I was your age I didn’t know what I wanted to be. So if some of you feel the same way, I sympathise.’

Seventy-two words. A school visit. Yes! What could be more fitting. In our last year of high school we were always being pestered with work experience opportunities. Wasn’t it entirely possible that Montag might have been sent to Clarisse’s high school to lecture the students on the joys of becoming a fireman? And wasn’t it even more possible that she thought he was hot? I imagined what kind of lecture Montag might give if he was recruiting teenagers for the fire department.

‘Paper burns at Fahrenheit 451,’ he told the class. ‘Flames curdle and blacken the pages till each book crumbles to ash. A library takes time to burn. The other firemen and I stand back and watch it together. We always know that we’ve done the right thing. We harvest the ash and use it as compost. In the fire brigade we value the future of this planet. Our creed is: we burn, so that you don’t have to. ’

Another seventy-eight words. My updated creed was a nice flourish. Bradbury was prescient but not quite so prescient as to predict global warming, recycling and the imminent extinction of the bumble bee.

I woke up at 6.30am and opened my MacBook Air. I’d been writing for nine days. Total word count: 6,762. By this time in 1950 Bradbury was reaching for the last dime in his bag of change. He spent $9.80 and produced a masterpiece. Why couldn’t I be a genius? The failure of my first novel hounded me. It wasn’t even worth $9.80. I couldn’t think of a plot. And I still wrote in disjointed fragments. My own life kept interrupting and changing the script. I wanted to get away from autobiography. I wanted to create with a capital C.What she ultimately ended up with instead is this book, a book about her failure to write her novel, and about her life to that point.

One day I caught a rare glimpse of some customers browsing the sex section. A group of teenage boys flicked to a large graphic image and asked, ‘Have you done this?’And her Acknowledgements at the end begin:

I didn’t reply. But I had.

This is a work of non-fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are, sadly, not the products of my imagination.The book also provides a much more fascinating take on Fahrenheit 451 than I suspect a pure re-write would have done. Dunn is able to comment not just on the book, but also on the Sparknotes (rather appropriately) commentary on the novel, Truffaut’s film interpretation but also the making of his film, and Bradbury’s own life and writing of the novel. Bradbury’s introduction from the 50th anniversary edition and the DVD extras for the film are as much her source as the book and film themselves: in part, she admits, this was driven by issues with the Bradbury estate, but its makes for a very satisfying meta-fictional – or should that be meta-non-fictional – experience.

‘Everything’s got a bit messy,’ Sooty said. ‘There are so many different characters and stories colliding in this corridor I don’t know how to keep everything straight. I’m just glad that we finally managed to crowbar something from Hans Christian Andersen into the mix again, because frankly the reference to ‘The Tinderbox’ has really been bothering me.‘But in reality, this is a wonderful debut book and strongly recommended.