What do you think?

Rate this book

836 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1928

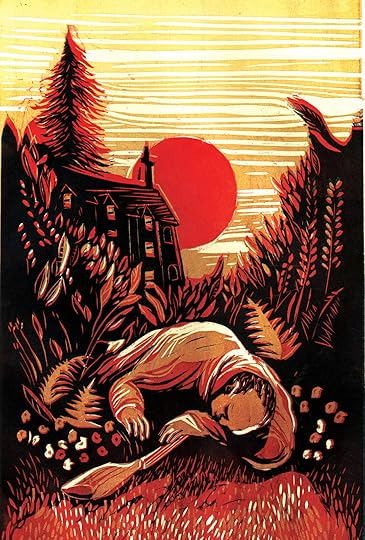

The miserable memory would come, ghost-like, at any time, anywhere. She would see Drake's face, dark against the white things; she would feel the thin night-gown ripping off her shoulder; but most of all she would seem, in darkness that excluded the light of any room in which she might be, to be transfused by the mental agony that there she had felt: the longing for the brute who had mangled her, the dreadful pain of the mind. The odd thing was that the sight of Drake himself, whom she had seen several times since the outbreak of the war, left her completely without emotion. She had no aversion, but no longing for him…. She had, nevertheless, longing, but she knew it was longing merely to experience again that dreadful feeling. And not with Drake….

These horrors, these infinities of pain, this atrocious condition of the world had been brought about in order that men should indulge themselves in orgies of promiscuity. That in the end was at the bottom of male honour, of male virtue, observance of treaties, upholding of the flag…. An immense warlock's carnival of appetites, lusts, ebrieties….

Immense miles and miles of anguish in darkened minds.

‘It's alto, not caelo…“Uvidus ex alto desilientis….” How could Ovid have written ex caelo? The “c” after the “x” sets your teeth on edge.’

It passed without any mention of the word ‘love’; it passed in impulses; warmths; rigors of the skin. Yet with every word they had said to each other they had confessed their love […].

When he had said: ‘I'd have liked you to have said it,’ using the past, he had said his valedictory […] her agony had been, half of it, because one day he would say farewell to her, like that, with the inflexion of a verb. As, just occasionally, using the word ‘we’ – and perhaps without intention – he had let her know that he loved her.

Noises existed.

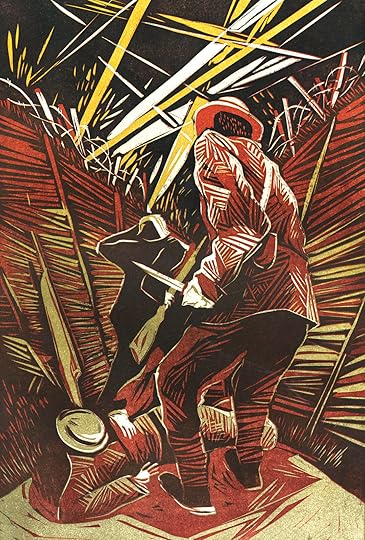

It's that they won't let us alone. Never! Not one of us! If they'd let us alone we could fight. But never...No one! It's not only the beastly papers of the battalion, though I'm no good with papers. Never was and never shall be...But it's the people at home. One's own people. God help us, you'd think that when a poor devil was in the trenches they'd let him alone...Damn it: I've had solicitors' letters about family quarrels when I was in hospital. Imagine that! ...Imagine it! I don't mean tradesmen's dunnings. But one's own people. I haven't even got a bad wife as McKechnie has and they say you have.The other – that the men who went to war, often because they were shamed and emotionally blackmailed by the society and even their loved ones, were, on their return, treated with suspicion and frequently hostility: “after the war was over, the civilian population would contrive to attach [determined discredit] to every man who had been to the front as a fighting soldier.”

Gentlemen don't earn money. Gentlemen, as a matter of fact, don't do anything. They exist. Perfuming the air like Madonna lilies. Money comes into them as air through petals and foliage. Thus the world is made better and brighter. And, of course, thus political life can be kept clean!...So you can't make money.The representation of upper class’ morality is fascinating: characters seem very preoccupied with the issue of who fathered who, and make most outrageous guesses; protecting oneself against STDs is what a gentleman does so as not to cast a bad light on his sphere – as we learn from the internal monologue of Christopher’s brother; central to the plot is the fact that gentlemen do not divorce, for divorce would mean “dragging one’s woman through the mud” - even when the woman is mud itself.

It was to him a certain satisfaction that (...) he hadn't lost one of the men but only an officer (...) for his men he always felt a certain greater responsibility; they seemed to him to be there infinitely less of their own volition. It was akin to the feeling that made him regard cruelty to an animal as a more loathsome crime than cruelty to a human being, other than a child.Self-control -“If you let yourself go …you may let yourself go a tidy sight farther than you want to”. It is Christopher's and Valerie's sense of responsibility which makes the main love scene of the novel look like this:

We never finished a sentence. Yet it was a passionate scene. So I touched the brim of my cap and said: So long!...Or she...I don't remember. I remember the thoughts I thought and the thoughts I gave her credit for thinking. But perhaps she did not think them. There is no knowing.Characterisation is formidable. Making Christopher relatable is short of a miracle. The contrast between Sylvia Tietjens, probably the single most fatale femme I have encountered in fiction, and Valerie Wannop, Christopher’s eventual lover, seems lifted straight from Jane Eyre’s Bertha and Jane (with the stipulation that little unfolds for the two women after JE fashion). The only thing the two women have in common is their good physical shape – sport for Sylvia being a way of maintaining her stunning figure and spending more time around men, for Valerie – a part of her moral, hygienic, modern education. Sylvia is compared to “the apparition of the statue of the Commander in Don Juan”, or a snake; she is “[radiant] and high-stepping, like a great stag”. She uses her sexuality to dominate, destroy, use men:

she ran the whole gamut of 'turnings down.' The poor fellows next day would change their bootmakers, their sock merchants, their tailors, the designers of their dress-studs and shirts: they would sigh even to change the cut of their faces, communing seriously with their after-breakfast mirrors. But they knew in their hearts that calamity came from the fact that she hadn't deigned to look into their eyes."Valerie, on the other hand, “seemed a perfectly negligible girl except for the frown.”

'I see what you're aiming at,' Sylvia said with sudden anger; 'you're revolted at the idea of my going straight from one man's arms to another.'

'I'd be better pleased if there could be an interval,' the Father said. 'It's what's called bad form.'

'[...]But just get it out, will you? Say once and for all that--you know the proper, pompous manner: you are not without sympathy with our aims: but you disapprove--oh, immensely, strongly--of our methods.'

It struck Tietjens that the young woman was a good deal more interested in the cause--of votes for women--than he had given her credit for.

'I don't. I approve entirely of your methods: but your aims are idiotic.'

'You don't know, I suppose, that Gertie Wilson, who's in bed at our house, is wanted by the police: not only for yesterday, but for putting explosives in a whole series of letter-boxes?'

'I didn't...but it was a perfectly proper thing to do. She hasn't burned any of my letters or I might be annoyed; but it wouldn't interfere with my approval.'

'Look here. Don't be one of those ignoble triflers who say the vote won't do women any good. Women have a rotten time. They do, really. If you'd seen what I've seen, I'm not talking through my hat.' Her voice became quite deep: she had tears in her eyes: 'Poor women do!' she said, 'little insignificant creatures. We've got to change the divorce laws. We've got to get better conditions. You couldn't stand it if you knew what I know.'

'I daresay I shouldn't. But I don't know, so I can!'

She said with deep disappointment:'Oh, you are a beast! And I shall never beg your pardon for saying that. I don't believe you mean what you say, but merely to say it is heartless. [...] You don't know the case of the Pimlico army clothing factory workers or you wouldn't say the vote would be no use to women.'

'I know the case perfectly well,' Tietjens said: 'It came under my official notice, and I remember thinking that there never was a more signal instance of the uselessness of the vote to anyone.'

'We can't be thinking of the same case,' she said.

'We are,' he answered. 'The Pimlico army clothing factory is in the constituency of Westminster; the Under-Secretary for War is member for Westminster; his majority at the last election was six hundred. The clothing factory employed seven hundred men at 1s. 6d. an hour, all these men having votes in Westminster. The seven hundred men wrote to the Under-Secretary to say that if their screw wasn't raised to two bob they'd vote solid against him at the next election...'

Miss Wannop said: 'Well then!'

'So,' Tietjens said: 'The Under-Secretary had the seven hundred men at eighteenpence fired and took on seven hundred women at tenpence. What good did the vote do the seven hundred men? What good did a vote ever do anyone?'

Miss Wannop checked at that and Tietjens prevented her exposure of his fallacy by saying quickly:

'Now, if the seven hundred women, backed by all the other ill-used, sweated women of the country, had threatened the Under-Secretary, burned the pillar-boxes, and cut up all the golf greens round his country house, they'd have had their wages raised to half a crown next week. That's the only straight method. It's the feudal system at work.'